When it comes to a legacy technology that badly needs to be disrupted, it's hard to imagine a better example than the college textbook.

It's big, heavy, expensive (often over $200), and -- as Matt MacInnis, CEO of the disruptive digital textbook company, Inkling, jokes -- "It's out of date before it even gets to the printer."

Students have to lug these anachronisms around in backpacks, only to read a chapter here and there as assigned by their professors. New editions appear every two or three years, rendering the older editions essentially worthless.

Second-hand bookstores do a thriving business on campuses as students try to stay within their budgets. Book-sharing, renting, and lending as well as illegal copying all occur as well.

A professor trying to teach from a core textbook in many subjects often finds it resembles the Winchester Mystery House, with chapters added on willy-nilly to a structure that originated many editions in the past, often decades ago.

MacInnis and Inkling seek to change all that, and, in the process, fundamentally transform the way students acquire knowledge. "Our goal is to redefine the way people learn from this kind of content," he says. "A digital textbook is not a book, it is software. So it's no longer about editions that come out every few years, it's about versions that you improve quickly whenever they need it."

It's also about the platform. Today, given that Apple controls 97 percent of the tablet market, Inkling versions of textbooks are available on iPads, but, MacInnis says, "in the long-term, as other tablets emerge, we will be platform-agnostic."

Consider the cost savings: Students no longer need to buy textbooks; instead they license software, paying only for those chapters needed at any particular time, at $2.99/chapter. Even if as many as 30 chapters are downloaded from a textbook, the cost would still be less than half the traditional purchase fee of a hardcover edition.

Publishers have the opportunity to shed those high production costs -- "the physical unit cost no longer exists," is how MacInnis puts it, adding that "the margins for publishers are fantastic, which is why they are happy to partner with us."

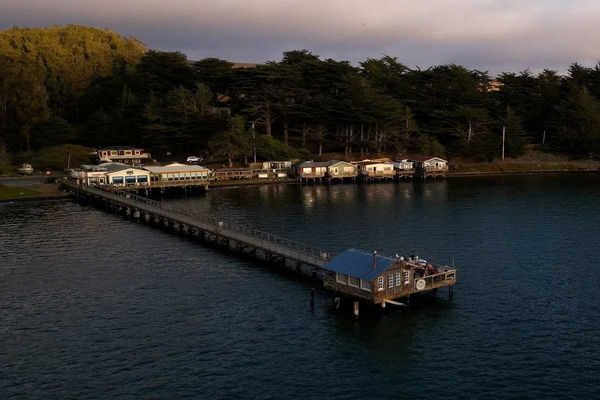

What's equally intriguing, however, is the interactivity embedded in the Inkling version. The photo at the top of this post shows how American history students can take a virtual guided tour of the slave trade on an iPad that gives a palpable sense of the horrors experienced by people kidnapped in West Africa and then transported to North America.

Eric Foner, author of Give Me Liberty!, says he is impressed by what Inkling has done with his book, which, by the way, is an extremely readable history text:

"What I like is that they do not try to add or change content, but make it easier for students to examine the text and images, and also access other things -- documents, videos, etc -- not in the printed version. Also, unlike some ebooks they do not clog up the narrative with all sorts of links. I think the narrative flow is one of the most appealing aspects of my book."

Among the 25 or so initial titles adapted by Inkling from major publishers like McGraw-Hill and Pearson, are music textbooks, where you can listen to a symphony while simultaneously tracking an integrated listening guide while scrolling in a synchronized fashion through the music.

At the end of chapters, assessment questions allow students to obtain instant feedback and correct mistakes in their understanding. "We believe they have a more engaged learning experience with our platform," says MacInnis, who prior to starting Inkling worked in Apple's educational division for eight years. "And our belief is that greater engagement equals better retention, (i.e., learning)."

Through Facebook, students can connect with friends studying from the same textbook and share notes; professors as well can share their notes in this manner, establishing what MacInnis calls a virtual "director's cut" of the learning text for their students.

Inkling's product is only nine months old and so far the total sales of digital textbooks ($50 million/year) represent only a tiny fraction of the overall $16 billion textbook market. But MacInnis sees that changing over the next few years.

"We'll have over 100 titles by the end of this year. And although there are thousands of textbooks, the key titles where all the revenue is concentrated measure only in the hundreds, and we're concentrating on those. I see the transition to digital ramping up in 2012 and to become financially interesting by 2013 -- when maybe 5-10 percent of the market (around a billion dollars' worth) will be digital."

MacInnis says one key reason the company is headquartered in the city as opposed to Silicon Valley is the presence of so many talented designers here. "When it comes to hiring fantastic software engineers, it's the same in San Francisco or Palo Alto, but we need incredible designers for our product and the top design talent is much easier to find in San Francisco."

He continues: "We love being a San Francisco company and share the same values this city has. We're trying to change the world and help improve learning in our society, and hopefully create a big business as well. There's no better place to do that than right here."