Many of us have grown so accustomed to using social networks like Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter to connect with each other, that we may have overlooked what research shows is a growing gap in our social lives, which is connecting with our neighbors.

Studies from the Pew Research Center have found that over half of all Americans don’t know any -- or only a few -- of their neighbors by name.

Looking to help change this modern dilemma is San Francisco-based Nextdoor, whose co-founder and CEO, Nirav Tolia, says, “We see neighborhoods as potential social networks, and an opportunity to bring something back that’s been lost in today’s society.

“Sometimes it seems that technology makes it easy to connect with people everywhere except when we step out our front door.”

Tolia and his team spent a year and a half building the technology and the features for Nextdoor, before quietly launching in late October. What they’ve come with is a free online platform that allows people to establish private, mini-networks in their neighborhoods.

A lot of the company’s focus has been to develop a service that is safe and secure and truly private – only real neighbors are allowed into each user-generated neighborhood group.

Creating and using an account, which is free, requires filling out an application and verifying your identity and that you live on the street you say you do. You then will have fifteen days to reach the minimum of ten neighbors for a group to be approved.

Once established, a group can admit any number of new neighbors and grow organically from there.

The site, which looks like Facebook, provides a map that you can use to set the boundaries of what you consider to be your neighborhood, which might be just a block on a street or an entire district.

For example, here in the city, Nextdoor Potrero encompasses 6,000 households currently, although that is an exception: Tolia says, “We think our system works best for groups from maybe 100 to about 1,000 neighbors.”

The mapping technology includes parcel and building outlines that neighbors can choose to populate with their real name and house numbers -- if they wish to. Since the only requirements for membership are your name and street name, it’s also possible to not reveal more specific details until you have a chance to build up trust with the neighbors who join you on Nextdoor.

“We tried to follow very closely what Facebook did in its early days,” explains Tolia, “so we’ve built this very slowly and carefully. It’s a piece of social software that people can use to solve real problems.”

So far many early users are helping one another with neighborly needs, like locating a babysitter, finding lost pets, or borrowing tools. “Probably 70 percent of the usage is what you might called ‘classifieds,’” says Tolia, “as if it is a combination of Yelp and Craigslist for neighborhoods.”

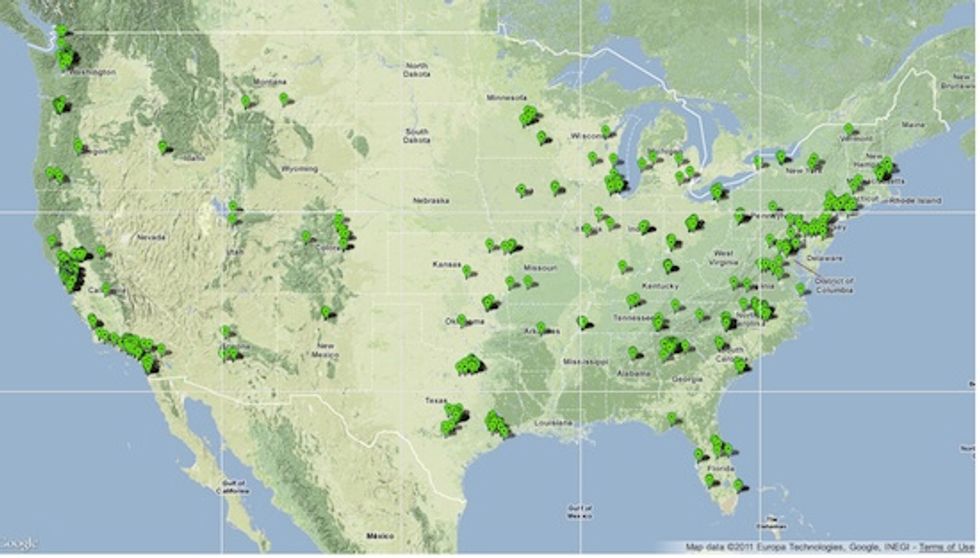

The service is available all over the country, and by the first five weeks after launch, Nextdoor was powering 550 neighborhoods in 40 states, with over 100 here in the Bay Area.

As for concerns that some of your neighbors might not be people you may not wish to get to know better, the site has a “no tolerance policy” for harassment, and prompts users to flag any objectionable post for immediate review.

But the main set of control is probably the requirement that a group cannot start until it numbers at least ten people who already know one another. This likely helps set a tone that will influence how any new members who subsequently join up will behave, since research shows people are normally sensitive to the social norms that are evident when join new communities online – at least when they have to use their real identities.

The Nextdoor team says local businesses are reporting increases in sales via the service, and that eventually its business model will likely hinge around connecting businesses with the people who live nearby.

In other words, with their neighbors.