When pondering the meteoric career of pop artist Keith Haring, the phrase “flash in the pan" is often uttered, but its relevance is up for debate. Dr. Timothy Leary, late psychologist and LSD poster boy, appreciated this description of his friend, despite its anticlimactic connotations, saying that it was a “good place to start." A mere decade in the making, Haring's skyrocketing trajectory, tragically cut short by AIDS in 1990 when he was 31 years old, surely qualifies as fleeting, but then again, his work—easily recognizable by its strong lines and kinetic nature—still makes an impact. On November 8, the de Young Museum unveils “Keith Haring: The Political Line," an exhibit that emphasizes the artist not just as an '80s icon (whose pieces feature, among other of-the-era motifs, break dancers and Mickey Mouse likenesses) but also as a full-throttle political force.

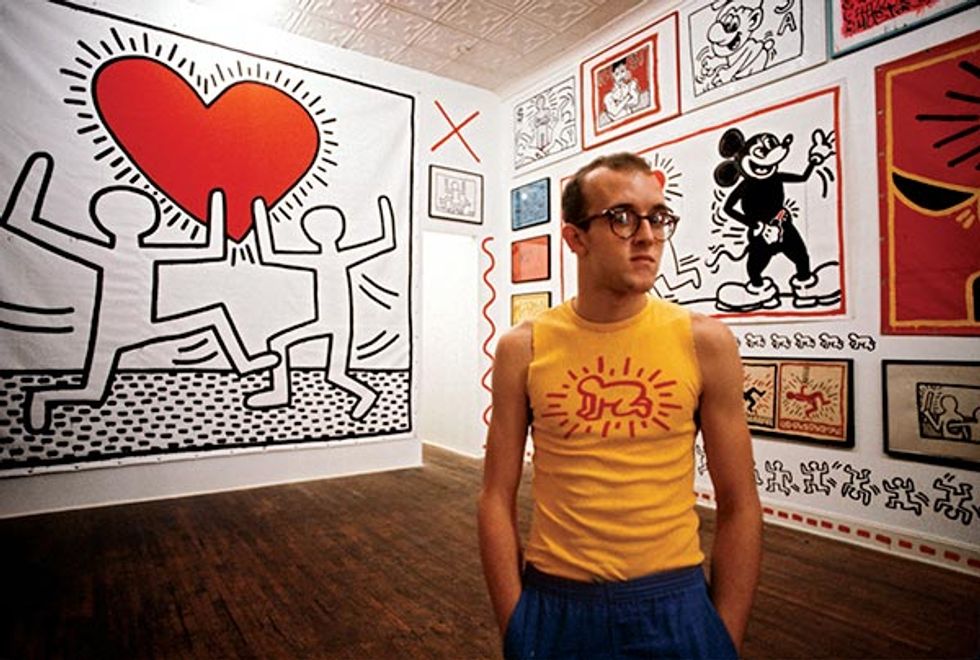

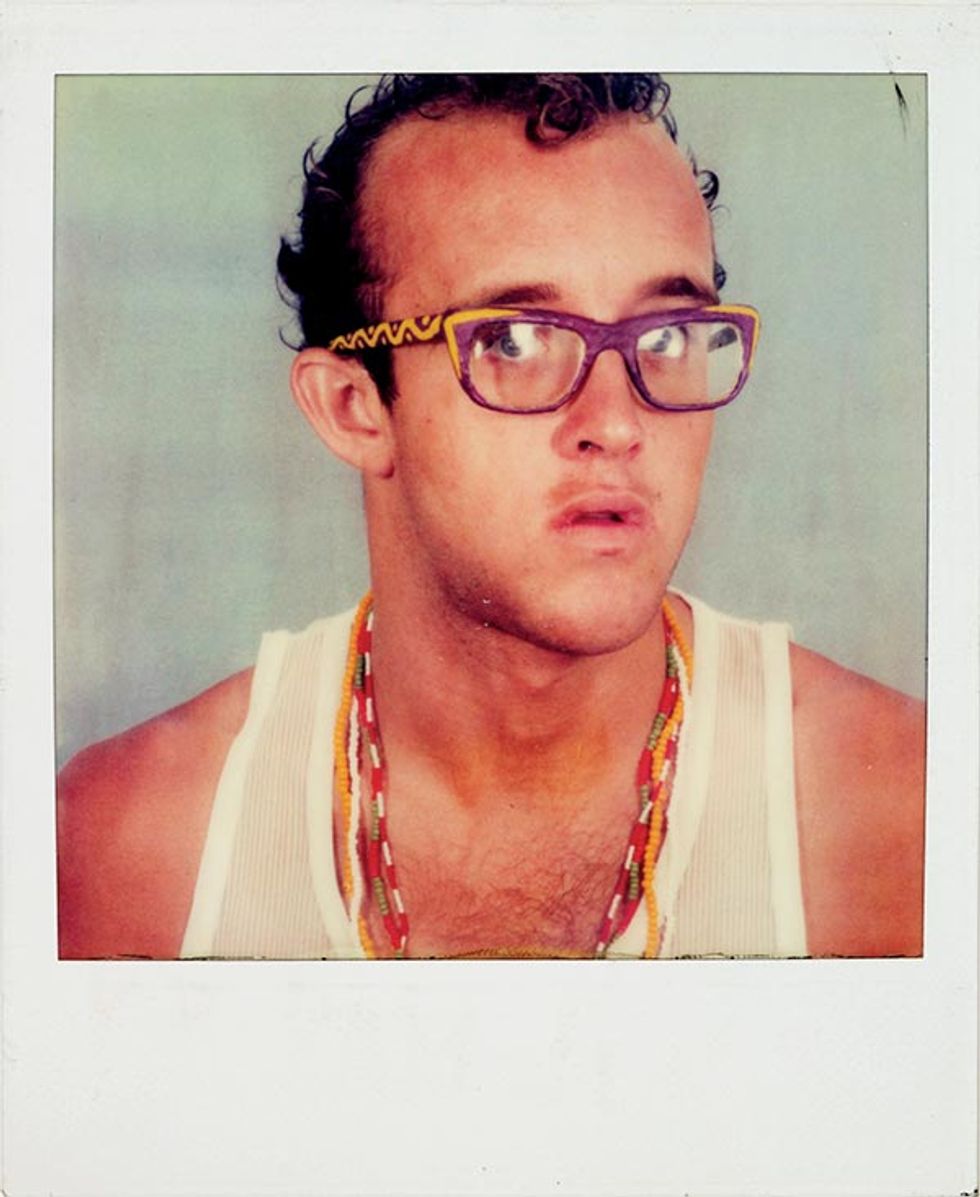

Julian Cox, curator at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, regards Haring's widely acclaimed October 1982 debut at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in SoHo as the single most defining moment of the artist's career. Photo: Allan Tannenbaum.

Raised in rural Pennsylvania, Haring identified as someone who, as he wrote in his journal (first published in 1996 by Penguin Books), “grew up on Pop, who watched television since [he] was born, who 'understands' digital knowledge." Though some may dispute the gravitas of work that unapologetically references pop culture (Haring was ever mindful of the “tightrope" he trod between “high" and “low" art), his iconography, which includes a spaceship, a barking dog, and a “radiant" baby, is tailor-made for delivering messages about AIDS, capitalism, nuclear disarmament, child welfare, and the environment. “All the issues he felt passionately about," says Julia Gruen, his longtime confidante.

At the renowned School of Visual Arts in New York City, Haring—a self-proclaimed former “Jesus freak" who subsequently rebelled against the born-again mores and small-town upbringing by adopting the lifestyle of a hitchhiking, drug-experimenting hippie—studied semiotics, the language of symbols. His confident and unbelievably fluid line—“the mark of an extraordinary draftsman," says Julian Cox, curator at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco—gives his work unique boldness and clarity.

Haring's spaceships symbolized a fear of the unknown; Haring created this action painting at the School of Visual Arts in 1978. Photo: collection of the Keith Haring Foundation.

In one of Haring's early subway chalk drawings, a barking dog—described in his New York Times obituary as an “alligator-like creature that looked as if it had emerged from an Aztec hieroglyphic"—shouts a warning against a televised nuclear explosion. Later, during a 1988 visit to the Peace Memorial Museum in Hiroshima, Japan (site of a World War II atomic blast), piles of anonymous skulls and wax figures with molten faces—a gruesome simulation of the effects of the bomb's heat rays—were indelibly seared into his memory. The daily download in his journal was distinctly woeful: “Who could ever want this to happen again?" he wrote. “To anyone?"

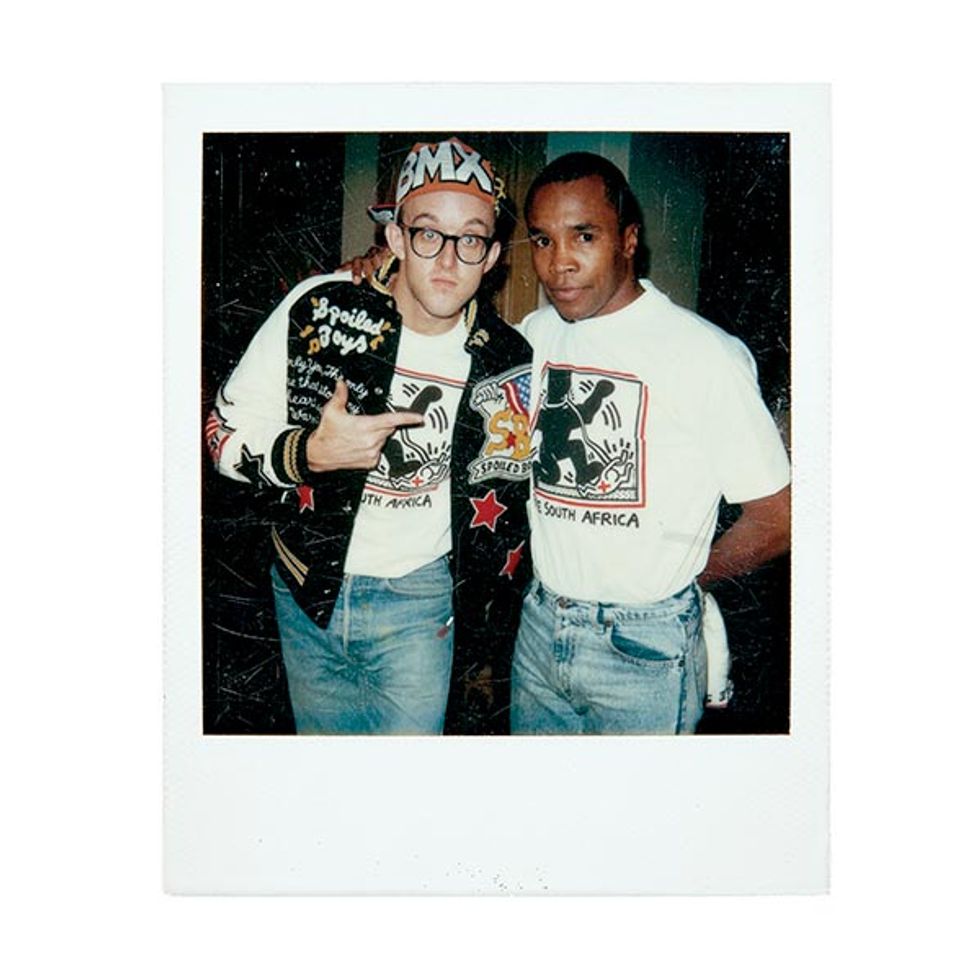

At a Central Park anti-nuclear rally in 1982, he distributed 20,000 posters featuring the radiant baby—a symbol of innocence and hope—trapped in a mushroom cloud, a trinity of angels descending upon him. And, Haring took a stance against racial inequality in the Free South Africa piece he drew for an antiapartheid demonstration in 1984. The work depicts a towering black figure, bound by a collar and leash, stomping on a diminutive white figure, who bears a shameful, Hester Prynne–inspired, red X on his chest.

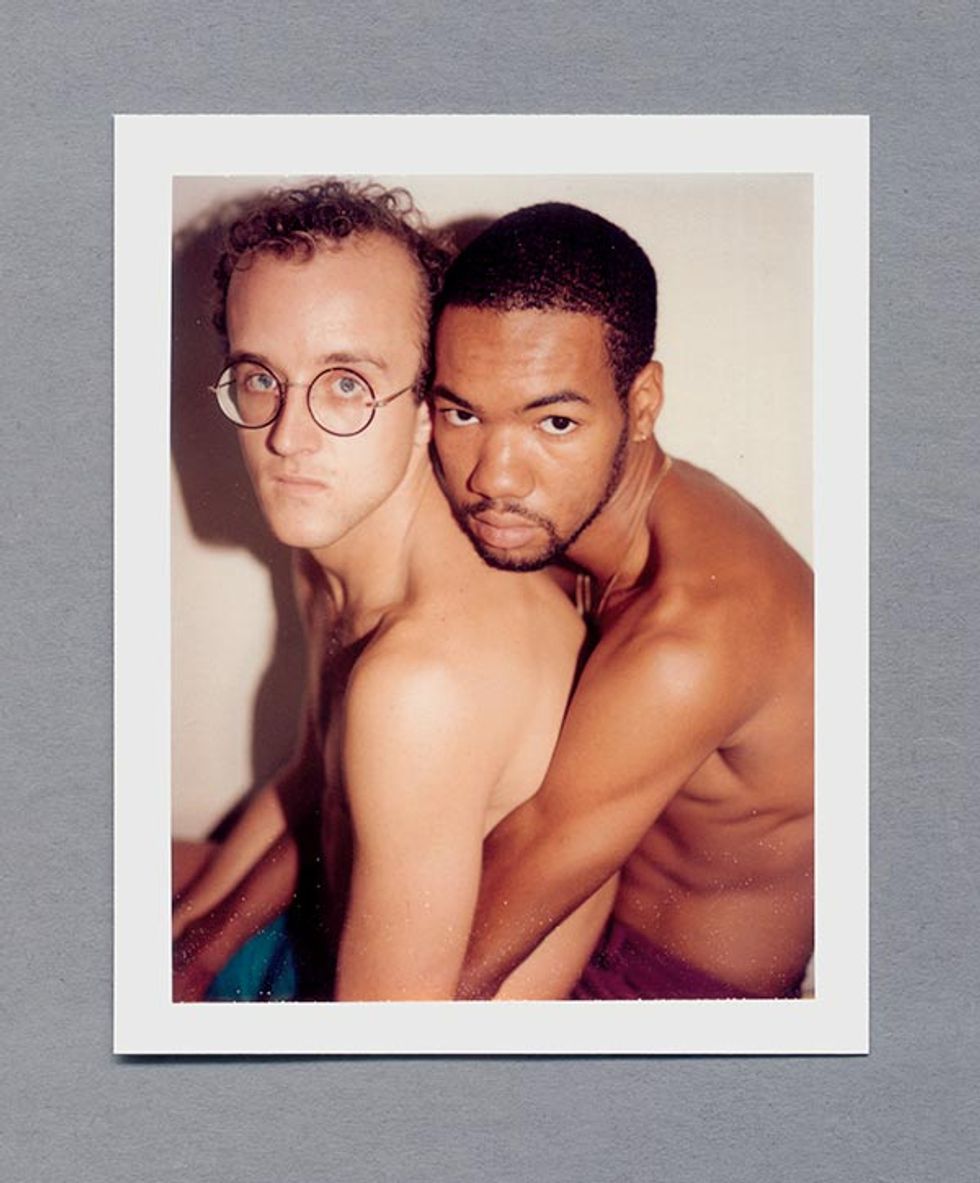

As Haring's friends, including one of his lovers, Juan Dubose, began to succumb to the AIDS virus, he painted the iconic Silence = Death canvas, which incorporated the pink triangle—a badge worn by known homosexual men in Nazi concentration camps—making it the prevailing symbol of gay awareness in the 1980s. Though Haring, who was openly gay, was an ardent advocate of safe sex (he created a series of Safe Sex posters from 1987 to 1988), he discovered in 1988 that he was HIV-positive. The Keith Haring Foundation, a nonprofit helmed by Gruen and headquartered in the artist's former NoHo studio, is dedicated, in part, to supporting HIV/AIDS education, prevention, and care. The Life of Christ, a bronze and white-gold triptych altarpiece etched with dense, interconnected markings of angels and humans reaching for Christ, permanently resides in Grace Cathedral's AIDS chapel as a tribute to those who have passed away from the disease.

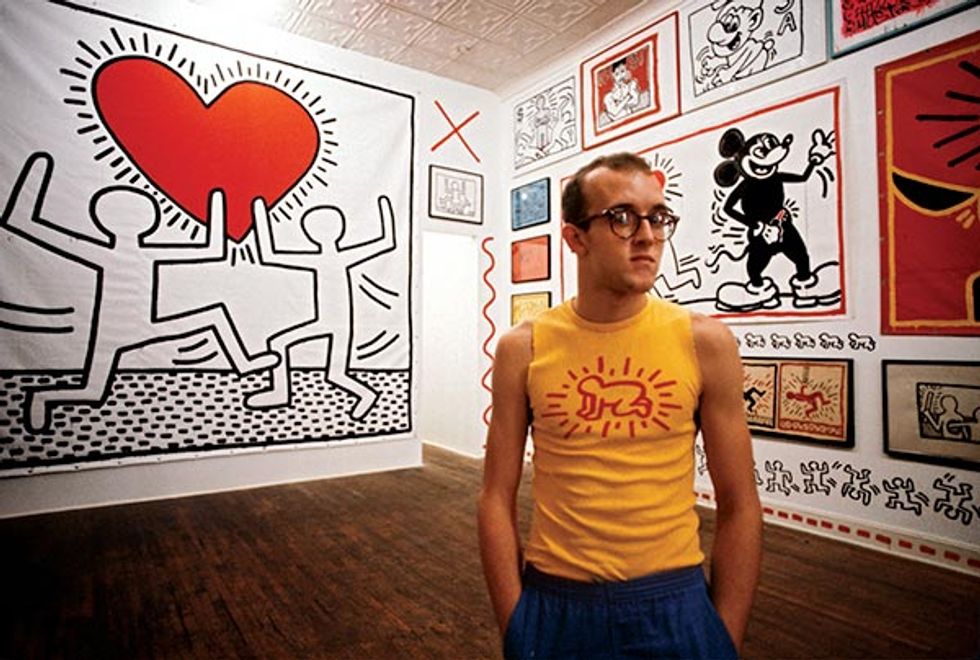

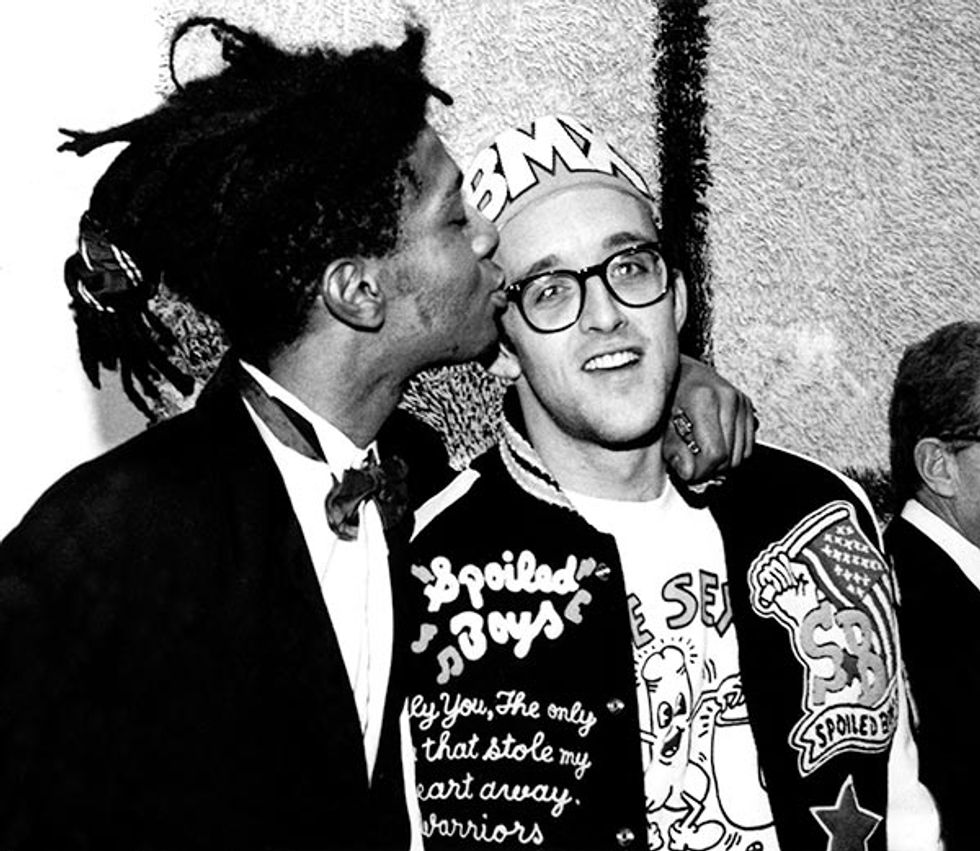

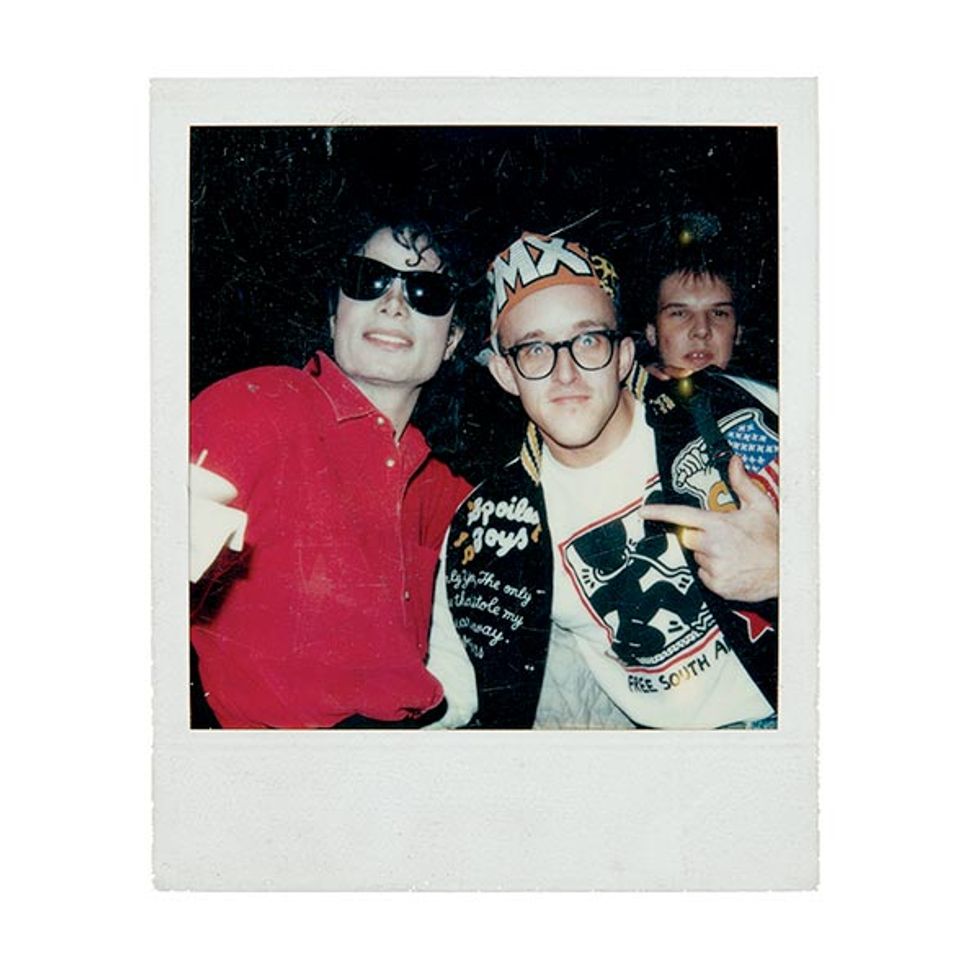

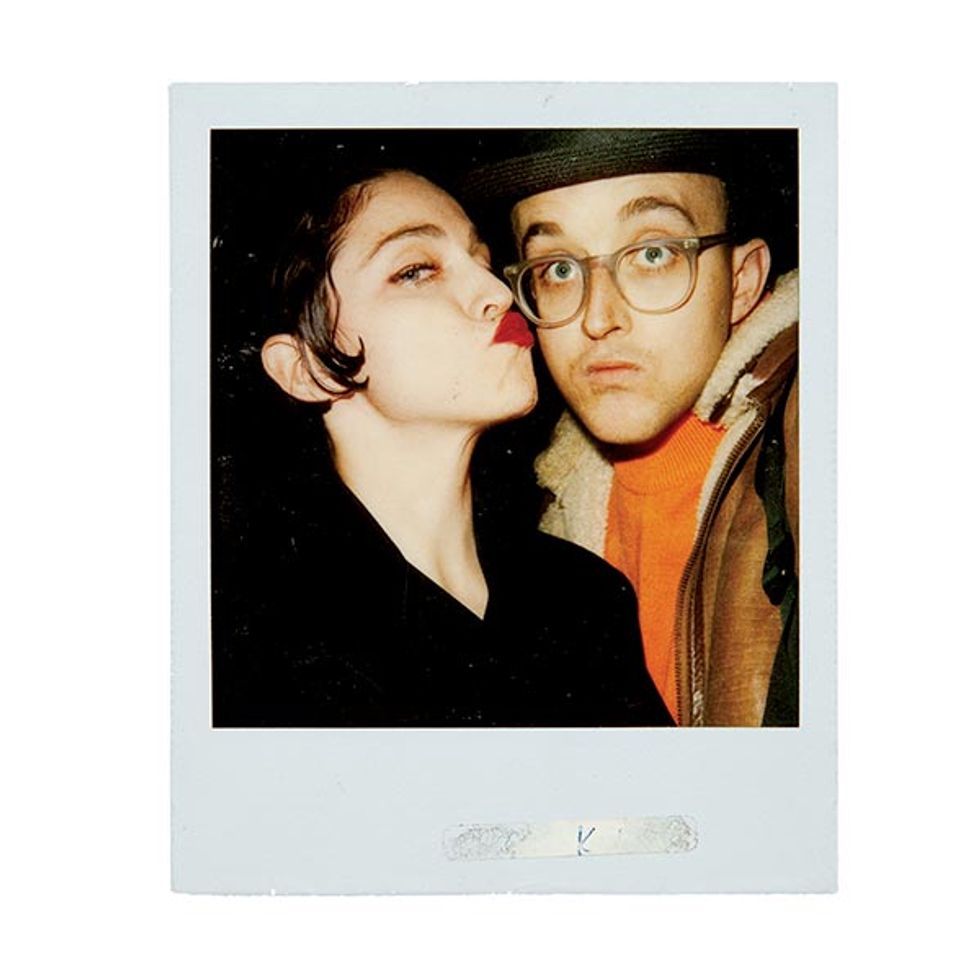

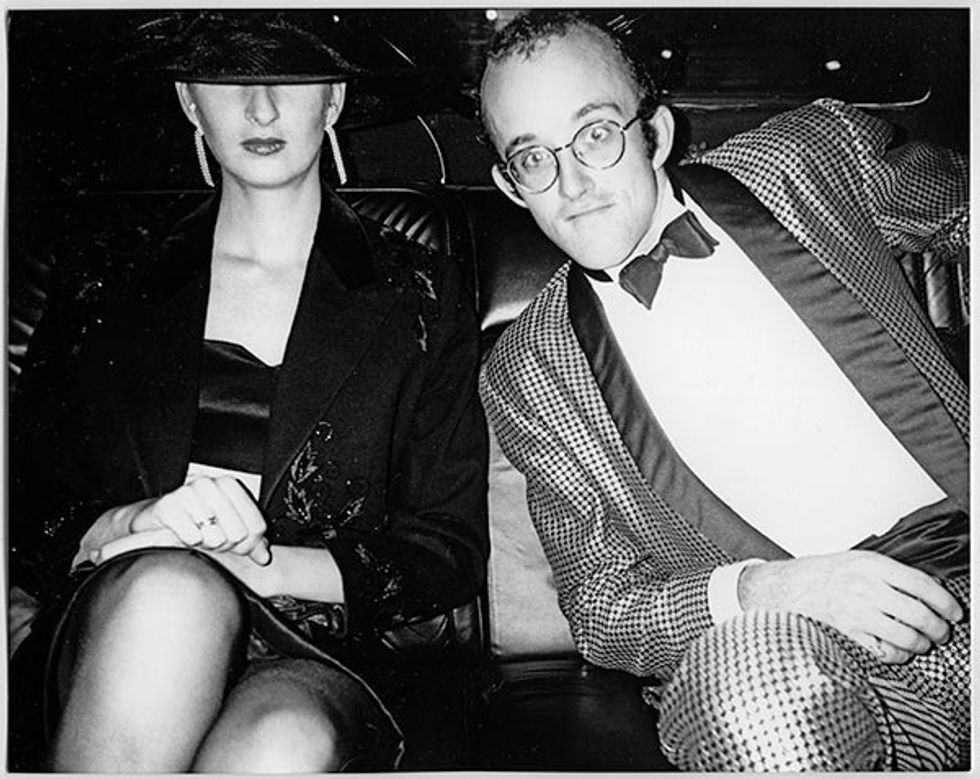

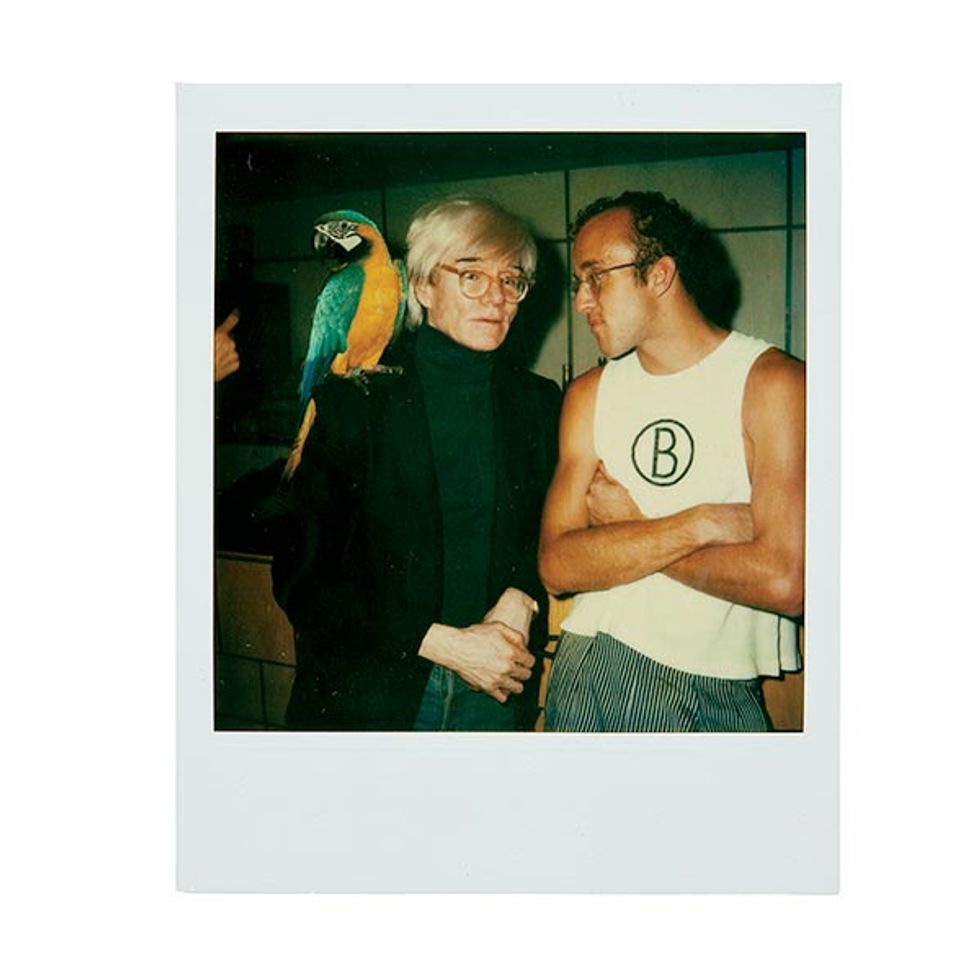

Although Haring's faithful activism stemmed from his compassion and moral compass (“Touching people's lives in a positive way is as close as I can get to an idea of religion," he wrote in July 1986), his messages were partly perpetuated by his high-profile fame and A-list Rolodex. After all, such celebrities as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Yoko Ono, Boy George, Madonna, and his mentor, Andy Warhol, constantly orbited around the consummate

socialite at New York's hot spots du jour, the Paradise Garage, Mud Club, and Club 57.

A wall in Harlem River Park turns into a PSA about the 1980s crack epidemic. Photo: collection of the Keith Haring Foundation.

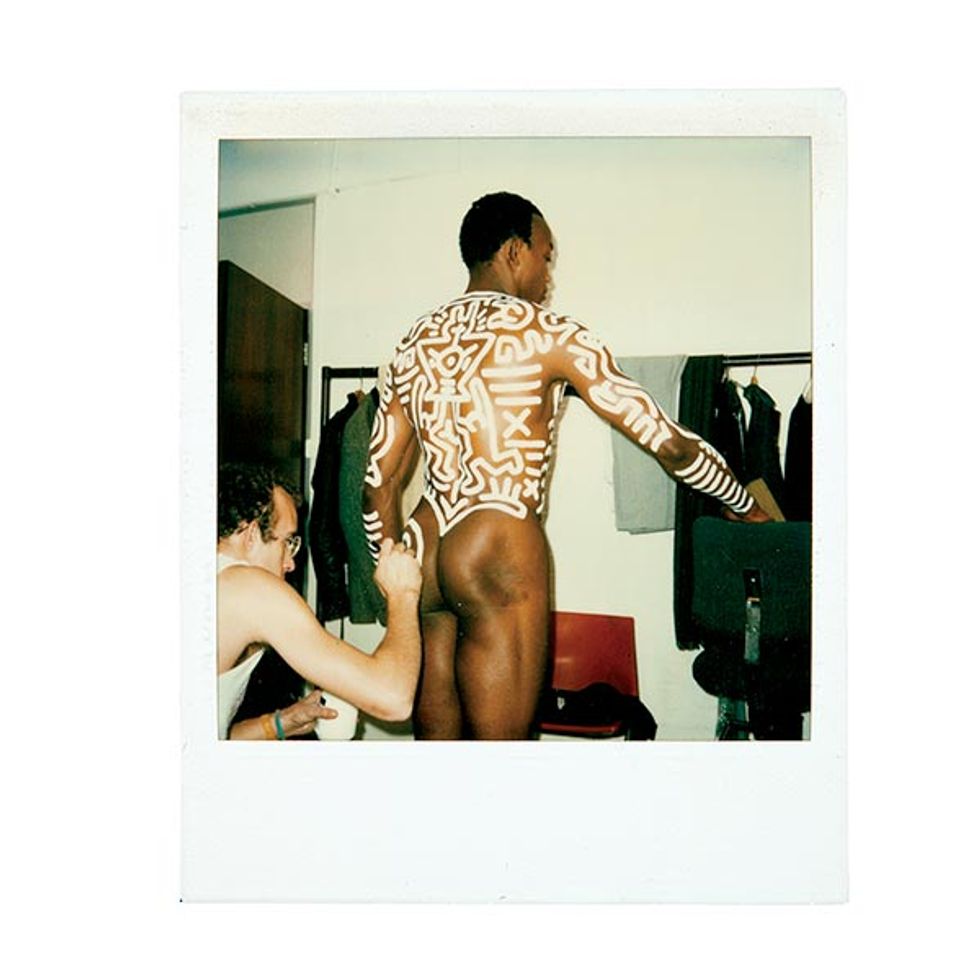

Haring made a point of spending Saturday nights at the Garage—where he watched break dancers and electric boogiers do their thing—even if it required a flight around the globe. Art consultant Jeffrey Deitch, who represented Haring's estate for 11 years, says, “Dancing was really part of the art experience—Keith didn't separate his focus on work from his enjoyment of life."

Haring's guerrilla art—from the hasty subway chalk drawings that triggered his notoriety to such large-scale works as the double-sided Crack Is Wack mural, painted on a handball-court wall in Harlem River Park—was also an unabashed attempt to broadcast his points of view. “For Keith, his medium is his message," said Leary, whose famous motto Just Say Know once marked the front door of Haring's art studio. “Keith could jump into one of his wall paintings and we'd never miss him, because the spirit of the artist is just merging with the magic that's suddenly appearing on the wall. It's metaphysical!"

Prophets of Rage, an acrylic on canvas from 1988, features a black figure breaking free from oppressive shackles to reclaim his rightful glory. Photo: collection of the Keith Haring Foundation.

Julian Cox has a more down-to-earth, contemporary take on the Haring phenomenon. “Keith was constantly devising ways to have his artwork—his message—seen by as many people as possible. He wanted to be an influencer," he says. “This is really just an early form of social media." Dieter Buchhart, the Austria-based curator of the 2013 Paris exhibition of “The Political Line," even likens Haring's iconography to emoticons.

His Untitled diptych (1981) “suggests the perils of unprotected sex," says Cox. Photo: on loan from the Rubell Family Collection.

“I imagine he was an inspiration for the computer industry at one point. He was just way ahead of his time," says Buchhart, who guest curated the San Francisco show, which will feature 25 works that were not exhibited at the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Among them are a 1984 Magic Marker–on–terra-cotta vase, a twist on ancient pottery designs, and Andy Mouse, a canvas from 1985 that pays tribute to two of Haring's heroes, Warhol and Walt Disney. A large-scale metal sculpture of three dancing figures, a permanent fixture at the Moscone Center, will grace the de Young's front lawn for the duration of the show.

The Andy Mouse character, often seen with dollar signs in its orbit, was born at the height of Haring's success. As much as he struggled with commercializing his work (a negative reaction to Reagan-era capitalism, evidenced by his caricature of the late president bearing the devil's triple-six calling card), Haring was also quite preoccupied with creating “art for everyone."

The Andy Mouse character was inspired by Andy Warhol, who helped the artist on his journey toward, and stuggle with, commercial success.

As such, Andy Mouse is often seen with dollar signs in close proximity. Photo: collection of the Keith Haring Foundation.

At his famous Pop Shops—one in SoHo (1986–2005) and one in Tokyo (1987–1988)—Haring devotees could stock up on such official merch as radiant baby buttons, barking dog T-shirts, and paper fans adorned with break dancing figures. The enterprise cued naysayers to emerge from the woodwork, crying, “Sellout!"

“The Pop Shop is an extended 'performance,'" Haring wrote defensively in February 1987. “It's about understanding not only the works, but the world we live in and the times we live in and being a kind of mirror of that." On the flip side, Gruen claims that some fans condemn the fact that Haring's art is exhibited in museums. “They tell me it's undemocratic, that it's elitist, and

ultimately a betrayal of his beliefs," she says.

Collection of the Keith Haring Foundation.

Although Haring's motives and strategies weren't always well received, much less understood, Leary believed that audience reaction to the artist was nuanced. “Keith may be controversial, but nobody really dislikes him. He may be shocking, subversive, offensive, but they all love him," said Leary, whose 1983 memoir, Flashbacks, Haring claimed “changed [his] life"—more than once. “They all know he's the kid on the block who's painting the walls."

How has Keith Haring inspired you? Tweet us your tales using #Haring7x7 by November 24 for a chance to win a one-year membership to the de Young Museum, plus a goodie bag of Haring swag.

This article was published in 7x7's November 2014 issue. Click here to subscribe.