With assurances of architectural beauty, community-encouraging measures, and easy transportation, is the planned Transbay District too good to be true?

If you believe the hype, Transbay District (the roughly 20-block area bordered by Second, Folsom, Main, and Mission Streets) will be the best thing to ever happen to San Francisco. If the final stages of planning go off without a hitch, something rarely achieved for a project so massive, this insta-neighborhood will be so hot that you’ll want to live there—or at least hang out at the restaurants and parks slated to be built.

The plans for the transportation-savvy mixed-use urban community have been on the boards for 20 years, and with the majority of the completion dates landing around 2020 (with some staggering all the way to 2030), it all seemed like a done deal until the SF board of supervisors voted in mid-September for a change in the tax structure based on a reassessment of property values, which have risen as much as 50 percent since the original deal was struck in 2006. Several of the district developers hit the as-yet-built roof after the vote, but no formal complaints or legal actions have been enacted. “We anticipate no impact to the construction schedule of the Salesforce Tower,” says Michael Tymoff, senior project manager at Boston Properties, a co-developer of the tower. “We are very hopeful something can be worked out.” Adam Alberti, a spokesman for Transbay Joint Powers Authority (TJPA), concurs, characterizing the action as a “move forward.”

When much of the old Transbay Terminal at First and Mission was taken out by the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, plans were already in the works for a new terminal—one to service the legion of buses running between the city and the East Bay and, for the first time in many years, house a train station, with a Caltrain line connecting SF to Silicon Valley. Not since BART began building its Bay-spanning tunnel in 1964 had the city tackled a tricky transit issue of this size.

But an interesting thing happened on the way to a new terminal. The state sold the parking lots that ringed the sites to pay for the construction—and developers eager to make their mark (and a lot of coin) hired notable architects who created a bevy of elegant, artistic, and, dare we say, important buildings (to land a deal, developers had to submit proposed designs). And to sweeten the pot, the property barons—Tishman Speyer, Boston Properties, and Related are just some of the heavy hitters on board—had to agree to include affordable housing, retail space, and green areas. The result is a civic-minded urban planner’s dream: Broad sidewalks with plenty of trees; a vibrant mix of shops and restaurants; walking trails and bike paths that crisscross the zone; and modern green space concepts—one park is being compared to New York City’s High Line, and the other is a five-block stretch under the bus ramp with groovy features, such as porch swings suspended from support beams). And there’s lots of housing—35 percent of which is set aside for low- and middle-income families—terraced housing, ranging from human-scale townhouses to high-rise buildings, promising an area that will be open and filled with light. Have you spotted the unicorn yet?

Maria Ayerdi-Kaplan, the executive director at TJPA, will have skeptics seeing pastel-hued, one-horned beasts all over the place. “The Transbay Transit Center itself will be a grand entry point to San Francisco,” she says. “The vibrant new neighborhood around it will be catalyzing—it will be dense but livable and walkable. With great architecture and parks, it will be beautiful. It will be unlike any other place in the world, but if I had to pick a place to compare it to, I’d say Vancouver, British Columbia.”

These are big promises—illustrated by slick videos on the project’s website (transbaycenter.org). In one, swelling cinematic music plays and renderings of the planned high-rises materialize before the “camera” swoops down over the Transbay Transit Center (TTC) and its 5.4-acre rooftop park, the artist-designed pierced metal skin of one high-rise, and the bold flower-motif floor of another. This is big—really big. Not only will it alter the city skyline for many, many years, it has the potential to further shift the consciousness of the city to SoMa and could rid the streets and highways of some vehicles. The architectural roster is populated with headline-grabbing names. When a state official was asked whether any other spot on the planet featured the work of starchitects Rem Koolhaas and Jeanne Gang in a five-block stretch, she paused before answering with a touch of facetiousness, “I don’t know of another place…maybe Dubai?”

Even John King, the San Francisco Chronicle’s sage architecture and urban design critic, is hard-pressed to find a discordant note in the project. While cautioning in believing developers’ hype and the promise of artistic initiatives, he says, “Transbay could add a whole new type of neighborhood to SF. It will create a genuine high-rise neighborhood rather than a bunch of autonomous buildings. There are really interesting spaces throughout—and the proposed design of the buildings could produce something different from slender shoeboxes that are stuffed with condos or apartments. It’s a place where people will want to live and, if they do live there, they won’t just be stuck in a tower because there will be a lively streetscape.”

When asked why he thinks denizens of SF (a city known for no-holds-barred development battles) are strangely silent about projects in the area, his answer is quick: “It’s because of the transportation piece. The factions that might normally protest this kind of development really like the transportation aspect of it.”

That piece is indeed considerable. Not only will Caltrain extend lines from Fourth and King Streets, the terminal will offer access to eight Bay Area counties. If and when high-speed rail comes to California, the terminal will also provide a link to Los Angeles. When asked if the number of controversial corporate buses could be reduced when the terminal opens, King responds, “Probably not,” and Ayerdi-Kaplan says, “Most certainly.”

Courtney Pash, project manager at the Transbay Office of Community Investment and Infrastructure, has a different view of why the city is embracing the project in its final stages. “The buildings are going up where there were parking lots,” she says. “It’s not like a community is being displaced. Instead, a community is being built where there was none before.”

Indeed, when all the haggling and the hammering quiet down, the city might just find itself with one of the newest and most important urban developments in America.

TRANSBAY TRANSIT CENTER

Building Notes: The $4.5 billion TTC changes the transportation game in SF, with 11 different transit systems coming together in one place (the players include Amtrak, BART, Caltrain, and Greyhound). It replaces the old terminal at First and Mission Streets.

Starchitects: Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects

What's to love: If you commute, you will appreciate being able to catch a ride closer to the heart of SF. But even if you never venture outside the city limits, you’ll be drawn to the 5.4-acre rooftop park, which will include cafes, trails, and a fountain with 1,000-foot-high water sprays triggered by the arrival and departure of commuter buses.

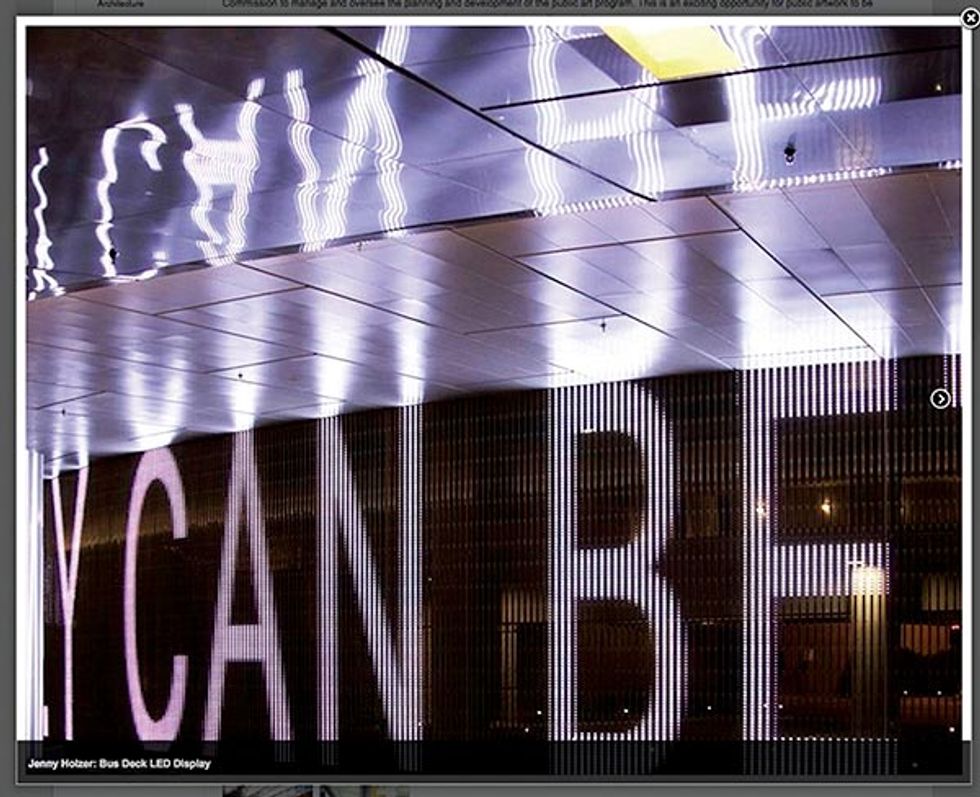

Design Highlights: The TJPA will spend $4.75 million on public art, defining its look and feel. A work by James Carpenter has glowing panels in the ceiling and on the floor. Local artist Julie Chang, who lives a few blocks away from the terminal, designed the terrazzo floor in the Grand Hall with eye-popping images of bright California poppies amid large geometric patterns. SF-born artist Tim Hawkinson has created the rugged abstract image of a 41-foot-tall man, which is being crafted with construction debris from the old terminal.

BLOCK 1

Building Notes: Situated at the corner of Folsom and Spear Streets, this marvelous twisting high-rise will have retail stores on the lower levels and condos on the remaining floors above.

Starchitect: Jeanne Gang, a Chicago architect, created what promises to be one of the city’s most unique structures. Gang was the subject of a laudatory profile in the New Yorker and earned a MacArthur Foundation fellowship and numerous design awards, including a 2013 National Design Award from the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum.

What’s to Love: Gang and her team looked at both historical photos and the SF of today, coming up with an idea based on an architectural motif that’s synonymous with the city: bay windows. “These windows are about orienting views to the outside and letting in light,” says Gang. “We took the idea of bay windows and rotated them slightly as they move up the building.” That sense of motion upends the traditional model of towers as merely stacks of boxes. Instead, you get a building that Gang likens to phototropism: the act of a plant turning to capture sunlight.

Design Highlights: The protruding and twisting windows will provide an interesting faceted effect. Instead of vast spans of mirror-like windows, the building will have many angles. “Light will play off the different surfaces, and the color and shading of the surfaces will change throughout the day according to the angle of the sun,” Gang says.

SALESFORCE TOWER

Building Notes: When complete, the Salesforce Tower, at 1,070 feet, will be the tallest skyscraper in SF and the seventh-tallest structure in the country. Named for its primary tenant, customer-management software maker Salesforce, it will radically change our skyline. Today when you come into the city from the Bay Bridge, you see a rolling cityscape, with the 853-foot-high Transamerica Pyramid topping the FiDi skyline. When Salesforce Tower is completed in 2017, your eyes will be drawn to the left of the pyramid to the new, and much higher, landmark and its neighbors, tipping the visual scale toward SoMa.

Starchitects: Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects

What’s to Love: For now, no one associated with the project is talking specifically about the details of Salesforce Tower. However, earlier reports describe housing an incredible, multimillion-dollar art piece that, as with the TTC, will be incorporated into the design itself. Dorka Keehn (a savvy art adviser who has engineered a wealth of public art projects, including The Bay Lights, Leo Villareal’s glittering Bay Bridge installation) and gallerist Wendi Norris are working hand in hand with architects to make that happen. The team hopes to announce the participation of an “internationally acclaimed artist” later this year. In an article published this summer in the San Francisco Business Times, an executive with Boston Properties said that artists have been contacted about creating a light installation that would be “visible throughout the Bay Area.” Odds are this stunning-sounding work of art would perch atop the tower.

Design Highlights: Stature alone might make it the crown jewel of the Transbay District, but the proposed dramatic, tapered obelisk top and the practices and materials that are forecasted to exceed LEED Platinum standards (in some published reports, wind turbines have been discussed) would make it a trophy building.

TRANSBAY 8

Building Notes: Transbay 8 is the working title for the project located on

Folsom between First and Fremont Streets, a mix of rentals and condos with retail stores housed on the lower levels.

Starchitects: The second time may be the charm for OMA, the Dutch firm helmed by Rem Koolhaas. The practice was tapped to build a Prada store here, but the controversial design went nowhere after the market crashed in 2008. This time, the New York arm of OMA will be heading up the project with local powerhouse, Fougeron Architecture.

What’s to Love: According to project developer Bill Witte, chairman and CEO of Related California, “Transbay 8 begins and ends with an urban gesture to the neighborhood and a desire to open the site to the public.” He’s referring to the midblock passage—a paseo—that links Folsom and Clementina. According to Witte, this will lend a sense of discovery and community to the project, which includes a tower and townhouses. The sloping sides of the tower let light flood the space. The townhomes, based on older SF homes but with a modern aesthetic, include that great architectural element that encourages gathering: stoops.

Design Highlights: It’s a podium building—one that includes multiple heights. On the Folsom side, the tower extends 550 feet into the sky, but at the rear, it features a row of smaller-scale townhouses along Clementina Street.

Renderings by Steelblue.

This article was published in 7x7's November 2014 issue. Click here to subscribe.