California writer JJ Mitchell writes of his experience as a volunteer entrenched in the refugee camps on the Greek island of Lesbos just before the recent wave of deportations began.

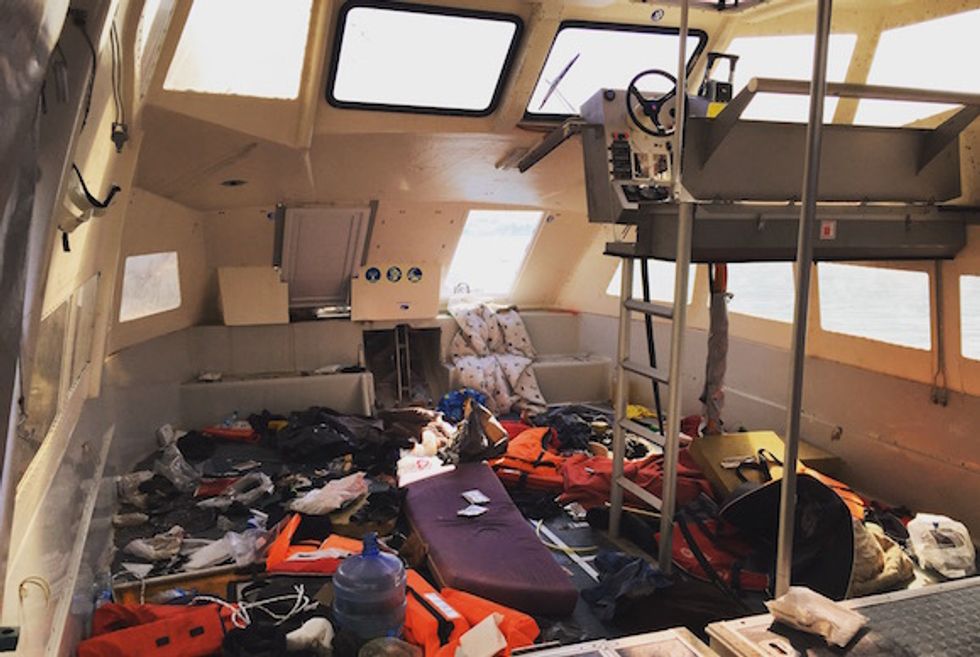

(Boats in Mytilini Harbour tell stories of the refugees they ferried from Syria and Afghanistan through the remains of what they left behind.)

Against the horizon, refugee boats in desperate pursuit of asylum present an unmistakable, lumbering profile; while in Mytilini Harbour, others confiscated by the Greek Coast Guard appear like a ghost fleet put to rest in some naval graveyard. Inflatable dinghies and small fishing boats mix with large, aging yachts. In the belly of one boat, life jackets, a lost shoe, a map, a bottle of medicine lay scattered. Before I arrived in Lesbos, I'd seen pictures of these boats, but it's the intangible parts—the smell of sweat, feces and gasoline—that startles me; their departures were so hurried.

I'm arriving in Greece as a volunteer, having just spent two weeks in the Calais Jungle—the so-called encampment in Calais, France where so many refugees are hoping to enter the U.K. I suspect the situation here is oversimplified and misrepresented by the press as it has been in Calais. These Greek islands are the front line of Europe's refugee crisis.

Life at Moria Camp

My volunteering experience on Lesbos begins at Better Days for Moria (BDFM), a volunteer camp established next to Moria Camp, where the government is registering incoming refugees. Occupying an ancient garrison, Moria Camp is all barbed wire and fences and a heavy presence by Frontex, the EU's border patrol agency.

As a BDFM volunteer, though, I'm here to focus on improving the quality of life for refugees in this temporary landing spot, where others like me are staffing a meager children's nursery, distributing dry clothes, maintaining a kitchen, and all around absorbing the increasing problem of overcapacity. The coexistence of Moria Camp and BDFM is uneasy. Weeks before I arrived, Moria Camp cut the water line to BDFM without explanation, making it even harder to provide basic waste and water services for people in need.

(Better Days for Moria is a volunteer-run humanitarian camp adjacent to the government run Camp Moria, where refugees were being registered, on the Greek island of Lesbos.)

I sign up for the 1am to 9am shift, and for the 5pm to 1am shift the following day, not yet realizing that, like this refugee crisis itself, everything is tentative, ever-changing. Along with the refugees, we volunteers survive and react by blurring news and rumors, and this state of uncertainty is often devastating. “We get no advance knowledge about any potential policy changes," BDFM coordinator Kerrie Moor explains. “I've had refugees ask me, just after being rescued, 'are we safe now?' How can we kill their spirit by answering no when they've come this far?"

Sitting around barrel fires to warm ourselves at night, we hear so many stories that demonstrate the incredible risks these refugees are willing to take to make it to Greece—risks from ISIS out of Iraq and Syria; risks from border guards, smugglers, harsh geography, from the mountains into Turkey and the Aegean Sea into Greece; and policy risks. They exchange stories and war wounds.

An Iraqi man shows the fingers of his right hand, stiff and black from frostbite, to an MSF (Medecins Sans Frontiers, or Doctors Without Borders) doctor, drumming them against a metal pole to demonstrate as they consult about amputation.

Mustafa, an Iranian music teacher who left his country carrying his tar, a traditional, six-stringed lute, friends me on Facebook as he shows me a video of himself playing. The smugglers he'd paid told him to run a 20 minute route across a snowy mountain pass to Turkey. Twenty minutes became 12 hours as Mustafa traversed freezing mountain terrain, placing his fingers in his mouth, alternating between his left and right hands, afraid that frostbite would end his musical career forever. He broke his tar is a fall down a ravine.

Another, a Yazidi father with his three-year-old daughter from Northern Iraq, motions to the feet of his little girl, clad in broken sandals. We find her a pair of new shoes and fresh socks, a backpack of toiletries, a scarf and blanket. ISIS took this man's wife and eldest daughter—no one has heard from them since.

BDFM is reliant upon donations and populated by volunteers—Americans, Danes, Norwegians, Swiss, British, French, Irish, German and Australians, some who, like me, stay a few days or a week, others who stay for months. We share one key thing in common: a deep frustration that governments are no longer willing or able to fulfil their humanitarian roles.

We do our best to teach the Syrian refugees who ask a bit of basic English: ferry ticket, passport, family, children. Asked to demonstrate “do you need anything?" one refugee smiles and holds up a cup of sweetened hot tea, Another her bowl of cold lentils. Everyone laughs, and I think how marvelous it is that this journey, with its dangers, uncertainty and heartbreak, hasn't destroyed their sense of humour. Soon we're all talking about home, which means something different to everyone. For a Pakistani man, it's Khuzdar, where he left his wife and son. For an Iraqi teenager, it's Sweden, where his uncle lives but where he's never been. For a Syrian family and their baby girl, it will always be Raqqa, where they one day hope to return.

And then worrisome rumors materialize. Ferries are suddenly closing to refugees, allocating only 25 percent of their capacity. Worried refugees form long roadside lines to begin the 7-kilometer walk from Moria to the port.

(What was once no doubt a landscape of mythic beauty, the cliffs surrounding the Korakas Lighthouse are littered with broken boats and life jackets.)

To the Northeast

With the southern and northern parts of Lesbos well covered by NGOs, the northeast coast represents a blind spot—most of its headlands and coves are either uninhabited or require four-wheel drive vehicles to reach them. I headed north to spend a couple weeks with the Coordination Kleio Team (CK), which coordinates rescue, medical and transportation with MSF and groups like Sea Watch. CK is an example of how seemingly ordinary people are self-recruiting to try and solve the extraordinary problems of this crisis.

Founded by Matt Llewellin, a British educator from Bristol, CK was initially organized to transport refugees on the rocky coastline and to circumvent the Greek mafia who were charging refugees exorbitant prices. “At first, I persuaded the mafıa types to let me transport mothers wıth babies and the dısabled. Over time, we were able to pay the locals themselves to drive refugees. It improved our goodwill with the villages, and it marginalized the mafia and opportunısts," Llewellin says.

CK operates out of a feta cheese factory that's been closed for the past year, generously given over to persuasive volunteers by its owner as a staging ground for the CK and MSF.

My first shift here is at Korakas Lighthouse, surrounded by the remains of several broken boats and life jackets. The scene is a lesson on the politics of this crisis, where the sighting of a refugee boat kicks off a sequence of broadcasts on Whatsapp, first to CK and then to the wider volunteer and NGO community. The VHF marine radio, which can be overheard by everyone including the Turkish Coast Guard, who use it to locate and turn back refugees, is the last resort, saved for such emergencies as boats in distress and refugees in the water.

From there, several of us headed to Limani harbour, where a ferry carrying 177 refugees, three times its maximum capacity, had just arrived after a standoff with the Greek coast guard. The ferry had been rescued earlier by a volunteer group of Spanish lifeguards called Proactiva, after veering dangerously close to the rocky shoreline.

But Greek coast guards had intercepted the rescue and forced Proactiva to cut their towline under threat of arrest. It took an exasperated Greek fisherman to diffuse the confrontation, and then tow the ferry to harbor himself. Onshore, we learn smugglers abandoned the ferry after leaving Turkey and forced one of the refugees, a woman who had been a municipal bus driver, to steer the boat to Greece.

Early the next morning, I hiked down to Theodoros Beach, a remote cove, accessible to land by refugees but hidden by steep headland from volunteers staffing the Korakas Lighthouse.

(The sad excuse for life jackets that are given to refugee children, left on the beach at Theodoros)

On this day, there are no abandoned boats or small fires to warm any arriving refugees. Only a surreal landscape of orange florescent life jackets and the carcasses of grey-black rubber rafts tell the secret of past landings. Many of the life jackets are counterfeit, filled with no more than three or four thin layers of foam that will do little to keep out water; the children's life jackets I find are little more than floaties designed for playing in the pool.

From the beach, I see how refugees would make their way inland, in some lucky cases on a shepherd's footpath, in others a headlong approach through thorny bushes and knapweed, highlighted by markers—a child's blue sweater, a muddy shoe, a knapsack, empty water bottles.

A few days later, I respond to a 3am call to Lagkada, a sheltered beach popular among smugglers who drop refugees off in groups of 30 under cover of darkness. Because Lagkada is so remote, we camp overnight, taking shifts to listen for the low drum of an outboard engine and the faint flicker of mobile phone screens. The refugees tonight are Afghans, a group from Kandahar and another from Jalalabad. At first, they suspect we're police but relax when we tell them we're here to help. One, a former journalist, has recorded most of the five-hour journey by video. While we wait for MSF transportation to arrive, we burn the life jackets for warmth and talk as though we had met under entirely different circumstances. Some text their friends while others take selfies with a bright flash. They ask us about Greek food and the nearest McDonald's.

By the time I leave CK, the first of several NATO ships are now visible in the water, and the refugee crisis feels like it's taking a turn for the worse. Many in Europe are viewing Turkey as the pragmatic solution, the boundary line to protect, as Macedonia has temporarily closed its borders, blockind the Balkans route.

(Yet another boat laden with refugees arriving on the shores of Lesbos)

At the end of my two weeks in Lesbos, on the morning I was set to leave, I take a long walk along the coast, almost halfway to the airport. Suddenly I recognize the unmistakable profile of a refugee boat arriving on the shore, and the rescue protocols I've learned reflexively kick in. I run to the boat.

I'm reminded then of the incredible instinct of humans to rise to the occasion in times of extraordinary hardship. How our humanitarian concerns unify us more than our individual politics. How a shuttered feta cheese factory can transform into a beacon of support. How even the most paralyzed among us can find a chance to laugh. // If you are interested in volunteering or making a donation towards supporting refugees, go to gofundme.com/freelifejackets or betterdaysformoria.com/donate.

[Editor's Note: Since this story was filed, Europe has reached a controversial agreement to begin to the deportation of refugees from Greece.]

--

J. Jason Mitchell is a sustainability advocate and essayist on environmental and socio-political issues, @jjason_mitchel.