Around the glass-walled pool at the envy rooftop bar, ripped boys and glossy-legged girls with straightened hair and skyscraper heels pick cocktails from a glowing menu. This is Medellín, cultural capital of the new Colombia—flush with oil money, cleaned up and ready to party (as seen on TV). But I am here for more than a caipiroska (a vodka-laden variation on the caipirinha). I want to know whether Medellín’s new image as innovation central goes deeper than the lip gloss.

“Imagine: This place pulled me away from New York,” says Conrad Egusa, a child of Cupertino who landed in Medellín with the idea of staying three months to learn Spanish. Eighteen months later, he’s running a coworking space called Espacio and touting Medellín as the future Silicon Valley of South America.

It’s a tough pitch. There’s no Stanford, no Berkeley Lab. But all the same, over a week in Medellín and the capital city of Bogotá, I see how much more humble efforts in public art, civic works, and small-scale innovations are transforming war zones into some of South America’s most visitable and livable places.

Egusa has joined the ranks of locals and newcomers rushing to make Medellín better. At Espacio, tenants such as the startup Intern Latin America and photography business Zefer Foto share glass-topped desks and breathe air freshened by a wall of plants straight from the cloud forest. The startup culture on display is part of why Medellín just won recognition this past March as the world’s most innovative city from the Wall Street Journal.

Down the street from Espacio, past, of all things, a four-year-old Hooters outlet, you can see Parque Lleras, a public park and happy hunting grounds of the young and single. The Charlee Hotel, designed by Arquitectura & Concreto, rises 16 stories off the plaza, looking like a mammoth shelving unit thanks to its zigzag facade in horizontal slabs of varnished lumber. Inside, every communal space is an art gallery. Blocks away at Carmen—perhaps Medellín’s most distinguished restaurant—diners settle in for the pesca del día (fish of the day) breaded in plantain powder and served with coconut risotto, grilled lime, rum raisin puree, green grape sauce, and fresh herbs.

But Parque Lleras and the rest of the upscale Poblado district, while a safe and delightful place to start, only hints at what’s happening elsewhere in this country of 47 million. It’s mostly grittier, a bit less visitor-friendly, and more exciting.

La Candelaria, Bogota. Photo by David Nicolas

Like here: Parque del Periodista in the sooty city center, late Saturday night. Emos, metalheads, and trannies mill around a memorial for a 1992 massacre. Club kids show up in black-and-white striped spandex, black wigs, and white greasepaint on their cheeks, looking like they popped through a wormhole from the ’80s. A powder-faced university girl offers homemade sweets for 25 cents, 50 cents for those speckled with pot leaf. A grizzled man sells candy bars from the top of a shopping cart and collects empty beer bottles in the bottom. A pair of cops in fluorescent green vests rolls through on motorbikes, ignoring the plumes of psychoactive smoke, and cruise on.

One afternoon, I meet Adriaan Alsema, a Dutch journalist who started the English-language news source Colombia Reports five years ago from his apartment a block from Parque del Periodista. He shows me into Bija y Barullo, a little Afro-Colombian collective hidden in a hallway off a bustling street. I order seabass smothered in creamy shrimp sauce. It comes with a salad of salted green tomatoes and fresh lulo (”little orange”) juice, the intense flavors piling one atop the next.

“Around here, people have created a sort of free zone,” he says. He describes the growing presence of barroom galleries and gay life in what a decade ago was a barrio left desolate by the drug war.

It’s here, in the center, that you find the city’s artistic ferment. Highways, subway lines, river, aerial trams, and dedicated bus routes converge. By day, hawkers on Avenida Oriental shout over the diesel motors of cane juice presses to offer roses, T-shirts, bootleg DVDs, baseball caps, Chilean plums, get what you will—usually for mil (1,000 pesos, or about 50 cents). In the median strip, mosaic tiles in the color palette of tropical fruit mark the crests and valleys of the avenue’s pyramids, built in 2007 by then-mayor Sergio Fajardo.

Throughout the center, pedestrians stumble onto the bulging bronze sculptures of local talent Fernando Botero. The most shocking is in Parque San Antonio, where an explosive charge in 1995 sundered a sculpture of a bird, converting its metal shell into shrapnel in an attack that killed more than 20 people and injured at least 100. The art is still there, next to a new, taller bird—the Pájaro de Paz (“Bird of Peace”) is a reminder that this country has yet to find peace as a five-decade, cocaine-funded insurgency continues to draw blood in the countryside. (Medellín was, after all, home of the late drug lord Pablo Escobar, who was taken out by Colombian authorities in 1993. Visitors can now tour Escobar’s grave and the house where he was killed.)

A Toxicomano mural in Bogotas Macarena District. Photo by Heiko Meyer

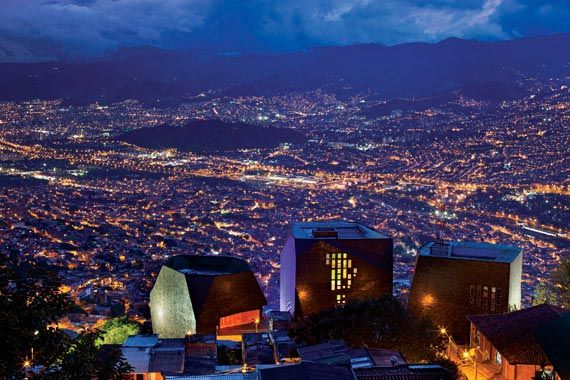

Medellín’s most important innovations aren’t found in tech startups or art collections but in public policy. Which sounds dry until you’re riding on the Metrocable aerial tram, soaring out of a subway station over shanties hanging off a hillside, the city bursting into view under ragged clouds. Gaze down at the narrow stairways that used to be slum residents’ sole route to work. Then look around in the gondola at seatmates who can now hold regular jobs. Suddenly, public policy seems as solid as can be.

Along with connecting the slums to the core, the city government has also gone to the ghettos. Tourists on the Metrocable usually debark at the Biblioteca España, a library of prismatic, charcoal forms that stands out over the slum. The Atanasio Girardot stadium is a spectacular feat of architecture and community building that draws skateboarders, tennis players, soccer teams, and swimmers. And these are just the most architecturally memorable sites. Dozens more sport fields and libraries are scattered across the city.

“Medellín has a social cohesion that is stimulated by the public sector,” Alsema says. While organized crime remains a major presence, the city’s transport links and libraries have given marginalized people a chance to enjoy the advantages of urban living, he says.

If Medellín is Colombia’s densest concentration of street fashion, art, and innovation, that doesn’t mean a traveler should skip past its bigger, chillier cousin. Bogotá, a 50-minute flight or nine-hour bus ride from Medellín, also pulls its weight.

For me, the first and most visible delight upon landing in Bogotá is the graffiti. As U.S. cities become more sterile daily, even the loafers-and-heels parts of Bogotá are never far from sprawling spray-can murals. The most remarkable are those by the Toxicómano collective, which works with wall-sized, socially conscious stencils.

A narrow belt from the central plaza to the northern suburbs carries visitors through a jumble of subcultures and historical periods, leaping from pre-Colombian metalwork to post-modern leatherwork and back again. From south to north, here are the greatest hits: Storytellers in the colonial neighborhood of Candelaria. The national museum, the modern art museum, and the Gold Museum. Leather goods made to order at César Giraldo’s workshop in the artsy Macarena district. Local craft brews at Nick’s in the gourmet ghetto known as Zona G. Charming mixed and gay bars, including the courtyard hangout Donde Esperancita in the neighborhood called Chapinero. The cafes of the restored colonial district Usaquén, and biking that area’s whole strip on Sunday, when the street Carrera 7 is closed to cars—Bogotá actually invented Sunday Streets.

A Botero Sculpture at Parque del Periodista, photo by Heiko Meyer

Hospitality is one of Colombia’s strong points. The national airline, Avianca, puts its U.S. colleagues to shame with clean planes and, wow, free checked baggage up to 70 pounds. Cabbies tend to be friendly and honest. Hoteliers compete for business—I ended up in the crisp sheets of the Alma Bogotá, an affordable boutique hotel with a rainbow-flag logo. Over a breakfast of perfectly ripe mango, banana, and papaya, a desk clerk and a fellow guest explained the city’s thriving theater scene. I rented a creaky old bike to explore Bogotá, and when I returned with a mechanical problem, the clerk volunteered to halve the price without my needing to ask for a discount. This attitude—treating people as humans and not as walking wallets—is hard to find in the excessively stratified societies of South America.

“Bogotá has gotten more international,” my friend Felipe tells me when we meet up. He takes me to Donde Esperancita, a courtyard bar where local gay couples, clumps of tourists, and university kids mingle over cheap beer. “The gay scene is new,” he tells me. There is even a “gay district” and a Gay Pride parade.

Of course, when a long-isolated country goes international, there are growing pains, especially with learning new languages. One bathroom warning I spotted deserves an award from Fail Blog: “Please don’t throw to toilet paper paper toilet or pads or any stuffs.”

But the country’s emergence is fostering increased national pride, which in turn is gradually bringing a locavore philosophy to dining. Chef Leonor Espinosa is leading this pursuit with her restaurants La Leo Cocina Mestiza and Leo Cocina y Cava, where she applies a fine-dining sensibility to surprising tropical products such as green plantain puree or leafcutter ants. Yes, ants. (Just close your eyes—you’ll never know.)

Meanwhile, Colombia’s famously fraught society is moving, albeit slowly, toward integration. Poverty—nationally defined as living on about $100 a month per person—is falling, and the government is seeking to make taxation a bit more progressive to increase social mobility.

Colombia’s tourist slogan is “The only risk is wanting to stay.” Considering the ongoing violence—I saw a bus driver chase a pedestrian with a hammer and touched the gravestones of children who had been killed in gang wars—I’d say that’s a stretch. (My prior visit to Colombia was dented when my host was drugged and robbed at a bar.)

Still, there is something to the place. My sense is that it’s more about the direction the country is moving in than where it is right now. In Medellín, in particular, a holistic attitude toward progress is steering the city in a healthy way. By the end of my trip, I was asking about rents and move-in deposits. So yeah. Maybe the risk is wanting to stay.

This article was published in 7x7's May issue. Click here to subscribe.

Related Articles