What if there were another planet, seemingly identical to our own, orbiting the same sun, populated by alternate versions of ourselves? That’s the question Mike Cahill and Brit Marling ponder in Another Earth, a quietly engaging drama that sounds, on the surface, like a sci-fi puzzle, one of those Isaac Asimov-inspired brainteasers bound to trip over its own complicated logic.

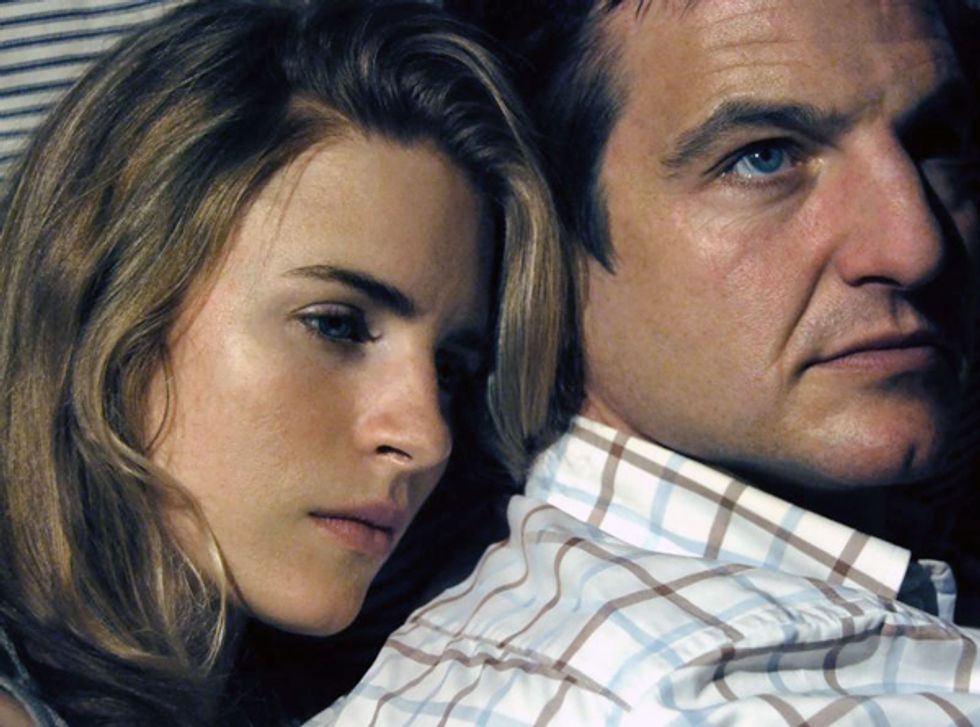

Yet Earth, which the 32-year-old Cahill directed, co-wrote, produced and edited, doesn’t concern itself so much with hard science as the very tender, human story it sets up. Marling, who shared writing and producing duties with her longtime creative partner, stars as Rhoda, an M.I.T.-bound teen who loses her innocence and her future in one tragic instant, drunkenly crashing her car and killing a mother and child.

Released from prison four years later, amid the fervor surrounding the maiden voyage to Earth 2 – where a carefully selected group will travel to make first contact – Rhoda dreams of a fresh start, preferably on that other planet. She applies to join the mission. In the meantime, she attempts to make amends, anonymously at first, to the husband and father (William Mapother, of In the Bedroom) whose family she destroyed.

For what might have been an exercise in high-minded fantasy, fraught with exposition and potential paradoxes, Earth is an intensely personal meditation on forgiveness and redemption. But that doesn’t mean Cahill and Marling, both left-brain thinkers who majored in economics at Georgetown, dismissed the science as a mere plot device.

Marling, who turned down a job at Goldman Sachs to pursue a career in film, laughs as she recalls her partner’s enthusiasm for the possibility of a parallel universe, where two versions of the same being could, at least in theory, co-exist. (“I think he believes it’s real,” she says. “I had to remind him we were making a movie.”)

Sure enough, Cahill, who, with his dark brown mane and beard, looks like one of the students from Real Genius, perks up when asked to break down the science that informed Earth.

“It’s all based on string theory,” he says. “The idea is that the universe is infinite – I guess Einstein proved that – but the particles in the universe are finite, so there we have a bit of an issue. The way [theoretical physicist] Brian Greene explains it, imagine a deck of cards shuffled an infinite number of times. Eventually you’re going to get an exact replica of what you started with.

“Mathematically speaking, the nature of the universe seems to suggest multi-verse – we have our universe, but there’s an identical one out there. So there’s not just one other earth, but an infinite number of them. You could travel to the farthest reaches of the galaxy and find a planet just like our own, and you might find yourself, reading the same sentence in the same article.”

Cahill acknowledges that the likelihood of such an encounter is pretty much nil – “That’s where we took liberties,” he explains – but it was enough to spark his and Marling’s imaginations. If you could meet another version of yourself, what would you say? What if your life played out in parallel universes like a Choose Your Own Adventure novel, but with infinite choices and consequences?

From that intriguing premise, Cahill began to visualize the story that would become the fulfillment of his longtime dream, which was never to become a banker. As a boy, armed with a Fisher Price camera given to him by his mother, he became “obsessed” with visual storytelling.

“Discovering how a montage works was a revelation,” he says. “I’d shoot a little Matchbox car, then shoot my brother behind the wheel of a real car, then cut back to the Matchbox car. The way the mind sutures that into a continuous sequence is amazing.

“Later on, I pretended to throw my brother off our balcony, but I paused the shot just as he was about to go over. Then I dressed up a bunch of pillows in the same clothes, shot the fall from another angle, and again the brain interprets it as if it all happens in one instant. At 7, that blew my mind.”

Hailing from a family of doctors, Cahill prepared for a career in medicine “for about two weeks” at Georgetown, then switched over to economics because it seemed easier. Filmmaking, he decided, would be his hobby. But neither Cahill nor Marling was able to subdue their creative impulses for very long.

After graduating, Cahill sat through a single interview for a banking firm (which he describes as “pure hell”) before landing an internship at National Geographic that ushered him into the world of documentary filmmaking. In 2004, he made his feature debut with Boxers and Ballerinas, an acclaimed chronicle of four Cuban youths, two in Havana and two exiled in Miami. Marling, who temporarily left Georgetown to participate, worked as his co-author and co-director.

Marling, 27, returned to school and briefly contemplated a post-graduate career at one of the nation’s most powerful investment banking and securities firms, but by then she too could no longer resist the allure of making movies. With no job and no fallback plan, she reunited with Cahill in Los Angeles, hoping not only to contribute behind the camera, but also to act. She relied on desperation to speed her pursuit of success.

Neither wanted documentaries to be their primary creative outlet. Cahill says the movies he shot as a boy were always based on his own fictional narratives, making Earth the obvious next step in a young, extremely promising career. For Marling, the appeal of fiction worked on two seemingly contradictory levels.

“When you’re making documentaries, it’s not you telling the story, it’s the world telling the story to you,” she says. “I appreciated the spontaneity of that, but as a means of personal expression, it’s limiting. I wanted to be more in control of the story, to make sure it had real meaning to me.

“But one of the reasons acting is so attractive to me is because you have to let go of your sense of self, your sense of time and the reality that surrounds you. You have to leave all your preparation behind and see what happens. And it’s so ephemeral – the minute you do something inauthentic, you’re back at zero. It’s either honest or it’s not. I think we’re often paradoxes in that sense. We’re attracted to the thing and its near opposite. We want control over how we live our lives and tell our stories, and we deeply desire something that’s going to take us out of control.”

Another Earth is now playing at the Embarcadero Center Cinemas and the Sundance Kabuki Cinemas. For tickets and showtimes, click here.