Creativity and innovation are hallmarks of San Francisco, where a startup mentality continues to define us. We routinely set foot on the hallowed grounds of storied cultural landmarks—unprecedented venues at their inception that remain progressive icons today. Here, insiders reminisce on the impact of four classic SF institutions to remind us why they epitomize the city’s special spirit. In this installment, we start with City Lights and The Fillmore. Next week, we'll continue with Castro Theatre and Stern Grove.

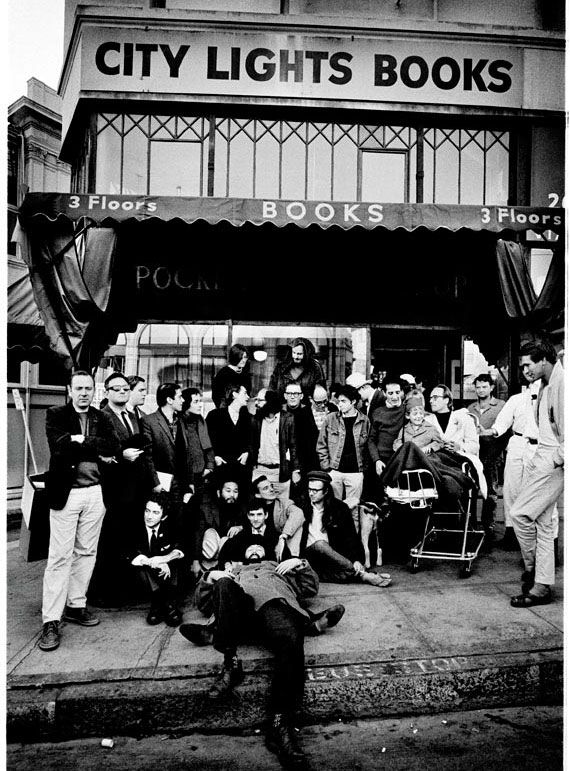

City Lights Bookstore, est. 1953. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, cofounder, publisher, and poet—As told to Chris Trenchard and Allison McCarthy

In 1953, San Francisco wasn’t what it is today. At that time, paperbacks were not considered real books in America. Peter Martin, an editor I met in North Beach, had the brilliant idea to open the first paperback bookstore in the U.S. My idea was to make City Lights a literary meeting place. I was used to the literary scene in Paris cafes and wanted to create a public place where people could hang out and read all day.

As soon as we got the doors open—we started off with one little room and slowly expanded—the store attracted people because there was such a void in that space. This was a brand-new scene. Back then, bookstores weren’t open on the weekends or late at night. We changed that. We were the first to introduce a periodicals section and the first to carry gay magazines. There was a lot of demand for this new culture, and we rode the wave. Comedians like Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl stopped in before gigs.

I was one of those New York carpet-bagging poets. I wasn’t really one of the Beats, but I got associated with them because I published them. City Lights, under my direction, was a publisher almost from the beginning, and this was another innovation—bookstores didn’t do that sort of thing. We printed Allen Ginsberg’sHowl in 1956, at the start of the poetry revolution. The Beats articulated what later became the themes of 1960s hippie counterculture, antiwar demonstrations, and ecological consciousness. Kerouac’sOn the Road was a sad book, but it turned everybody on because it expressed what his generation was feeling. Sociologists said it articulated the end of American innocence.

In the late 1990s, we restored the City Lights building because of a required retrofit, but the inside remains mostly the same. You’ll still see locals reading in the basement or up in the poetry room. We have so many events there, but the tourists don’t generally know about them—they’re just passing through. We also get a lot of professors and students from all over the country and an enormous amount of foreign visitors. Today, there’s not a literary revolution as there was when City Lights opened. Today, we have the electronic revolution, which is wiping out so many bookstores. We’re benefitting from being among the few that have survived. We could soon be the last man standing.”

The Fillmore, est. 1966 Joel Selvin, San Francisco Chronicle music critic, 1972–2009, -- as told to Allison McCarthy and Chris Trenchard

"I saw my first show at the Fillmore in 1967: Chuck Berry and the Grateful Dead. It cost $3 to get in. There were two walls covered with lights. The stage was small. About 1,100 people, absorbed in sound and lights, crammed into the room. The experience was truly authentic."

"And to think that bands like Led Zeppelin, The Doors, Otis Redding, Howlin’ Wolf, and the Grateful Dead all played on that tiny little stage. Bill Graham started renting the place from promoter Charles Sullivan in the ’60s. The thing was a success right from the word 'go.' Bill wasn’t really a fan of rock music—he was originally a mambo dancer from New York. But he had plenty of street smarts. Over time, though, he figured out how to book that room. It became a tribal rite to play there, and that gave the Fillmore this kind of mystique. Groups like Traffic and Cream gave performances that ended up being fundamental to the acceleration of their careers. It became clear that this place was at the center of something very special. At the time, Chet Helms operated the Avalon Ballroom, which was the Fillmore’s primary competitor back then. He had this theory that the Fillmore’s Apollonian stage and proscenium were gateways to the gods. Promoters would leverage this mystique to get bands like Crosby, Stills, and Nash, who would normally play at much bigger theaters. Then in the early ’90s, Tom Petty played 20 or 30 shows there over the course of a few months. Petty was definitely building on that mystique. It was quite a different place then. The old stage now lies (almost completely hidden from view) underneath the newer, bigger stage. But the Fillmore is still a space steeped in history and the ghosts of great performers. The guy who does the booking now, Michael Bailey, really knows the thrill of fandom. He’s been shrewd about capitalizing on the legacy of the Fillmore in the ’60s. Bands today are aware of the mystique—who hasn’t heard Cream’s Wheels of Fire: Live at the Fillmore? And it’s still a damn fine place to see a show.”

This article was published in 7x7's June issue. Click here to subscribe.

Related Articles