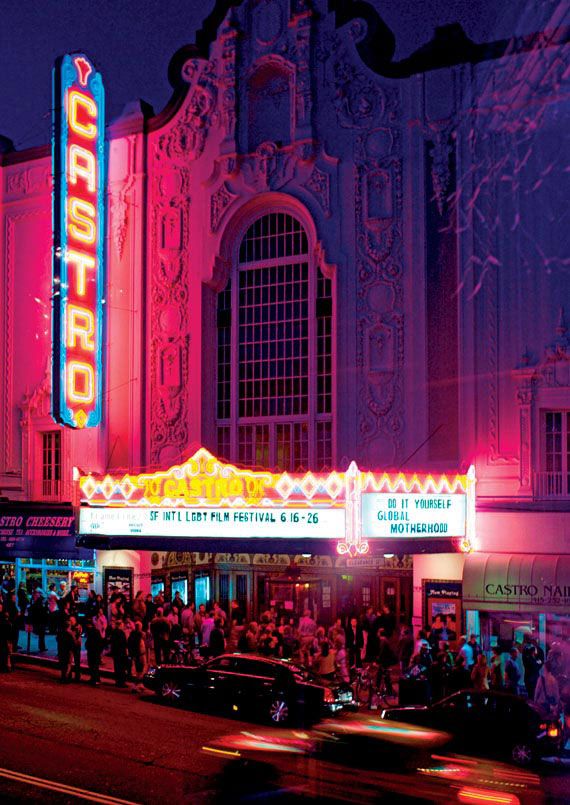

Creativity and innovation are hallmarks of San Francisco, where a startup mentality continues to define us. We routinely set foot on the hallowed grounds of storied cultural landmarks—unprecedented venues at their inception that remain progressive icons today. Here, insiders reminisce on the impact of four classic SF institutions to remind us why they epitomize the city’s special spirit. In this installment, we continue with Castro Theatre and Stern Grove. Last week, we began with City Lights and The Fillmore.

Castro Theatre, est. 1922. By Jenni Olson, filmmaker and former

codirector of the

San Francisco

International LGBT

Film Festival

The Castro was built in 1922, by a renowned architect named Timothy Pflueger, to rival every other movie house in the city. Since the theater has a history that goes back far before my time here, I’ve spent a lot of time over the years asking questions of folks like Allen Sawyer, who was the manager in the late ’70s. I recall him saying that even before the Castro showed gay movies, they were catering to gay audiences with movies starring Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. That evolved into showcasing films by gay directors like Andy Warhol, John Waters, [Jean] Cocteau, and [Pier Paolo] Pasolini. One of the biggest gay film events in the Castro’s history was the 1985 world premiere of Arthur Bressan’s Buddies—it was the first dramatic movie about AIDS.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the theatre had some of the best and most successful repertory programming in the country. For 17 years, [programming director] Anita Monga and her team brought in high-profile content like the 25th anniversary premiere of The Godfather in 1997. They also maintained solid house fare like Citizen Kane, Blade Runner, and All About Eve.

The experience of seeing a movie at the Castro is unparalleled. The grand Wurlitzer organ has always set it apart. The house organist David Hegarty, with his preshow performance, is a trademark of the place. It still gives me goose bumps when he launches into “San Francisco,” which is always the last song before the show begins. The Wurlitzer descends below the stage, the lights go down, and the crowd applauds. I’d say it’s one of the reasons that Castro audiences are so actively engaged in the experience.

The Castro has been host to so many of the city’s top film festivals—it is the anchor venue for the LGBT, Asian American, and Jewish festivals, as well as a primary home for the SF International Film Festival and the Silent Film Festival. For me, it is a place of community and fond memories—the walls of the theater actually contain some of the ashes of my mentor, the late Vito Russo. He was the author of a book called The Celluloid Closet. It was a pioneering exploration of homosexuality in the movies and was later made into a documentary.

The theater certainly has a place in the hearts of LGBT movie lovers just because it is such a jewel in the heart of the Castro. Among LGBT filmmakers, it has an international reputation. As a filmmaker, showing my films here has always been the ultimate experience. The venue is spectacular, but really it’s the audiences who make it the most fabulous place.”

Stern Grove Festival, est. 1938. By Doug Goldman, Stern Grove Festival Association chairman of the board

I’m the fourth generation of my family to head this festival. In 1931, my great-grandmother, Rosalie Meyer Stern, bought this property at 19th and Sloat with the purpose of deeding it to the city to become a park. A few years later, she had an idea: Present free concerts in the beautiful meadow she had donated to the city in 1932. You see, she was very involved in the community of San Francisco. This was still the post-Depression era, and the SF Symphony only performed in the winter months, so they made no money in the summer. My great-grandmother saw this as an economic opportunity for the performers. She also saw it as a great way to promote the park. These concerts could attract a huge number of people who couldn’t otherwise afford to see live music. The SF Symphony performed twice in 1938, the inaugural year of the festival.

Audiences think the artists perform for free. They think the sound company is free. They think everything is free, but in fact, the Stern Grove organization pays for everything. We rely on endowments, legacy funds, and donations to keep this thing going. In 2003 and 2004, we ran a campaign to raise the $15 million necessary for a park renovation with architect Larry Halprin. It’s this kind of community support that will hopefully enable us to expand beyond our 10 consecutive Sunday concerts. One hope is to supplement music programs and education in public schools, but we’ve got a long way to go.

This season marks the Stern Grove Festival’s 75th year—it has become part of the fabric of San Francisco. In the beginning, we hosted the symphony, ballet, and opera. One of the bigger names to perform in the 1960s was Arthur Fiedler of the Boston Pops orchestra, and then in 1969, the Preservation Hall Jazz Band started playing at the grove and performed for 30 years straight. Attendance has a lot to do with the artists on stage. The E Family (all the Escovedos), Anita Baker, or Diana Krall will bring out big numbers, and the weather makes a difference. A good weather day will bring out at least 10,000 people.

I’ll never forget the Tabla beat science concert in 2001. It was a world premiere, but what was most memorable was that the clouds parted and the sun streamed down onto the stage as soon as the music began. It was beautiful. We also hosted Los Van Van, the legendary Cuban group. We really reached a lot of new people. It’s pretty rare to have an enterprise that cuts across all lines—age, ethnicity, education, income—and I’m so grateful to be a part of it.”

This article was published in 7x7's June issue. Click here to subscribe.

Related Articles