The French company Ubisoft, which is the world's third-largest game developer, maintains its local headquarters at 625 Third Street, and is about to launch what may prove to be a revolutionary new game next month called Rocksmith.

Now, bear with me here. I'm not one to throw the adjective "revolutionary" around loosely. First, as a former 60s activist, I'm keenly aware of how overused that term has always been, and how rarely anything (particularly a product) described as revolutionary actually turns out to be so in the real world.

But this time, the adjective may prove fitting.

First, some context. Remember Guitar Hero? Or the large number of imitator games that followed?

I'll never forget the day I walked into a startup in 2008 in downtown Redwood City, where I first watched a bunch of geeks playing fake guitars, perhaps seeking to replicate the emotional high of being an actual rock star, albeit before a virtual crowd.

Having spent some time around actual rock stars, back in the 70s, when I was a reporter and editor for Rolling Stone magazine, this aspect of gaming culture immediately fascinated me.

Laurent Detoc is the man in charge of Ubisoft's office here, with 345 employees presently, and he kindly walked me through the company's evolution over the past quarter-century. It can be neatly summarized in a list of AAA games and brands, like Rayman, Tom Clancy, Splinter Cell, Assassin's Creed, Just Dance, and Prince of Persia.

But what really lights up Detoc's eyes these days is the impending release of Rocksmith.

"This game represents a defining moment for us," Detoc told me. "Because it will speak to people on an emotional level that has not been touched before. Even as a middle-aged man, I think there's something to be said about how we all still want to be a rock star. Everybody, at least secretly, wants to be a rock star."

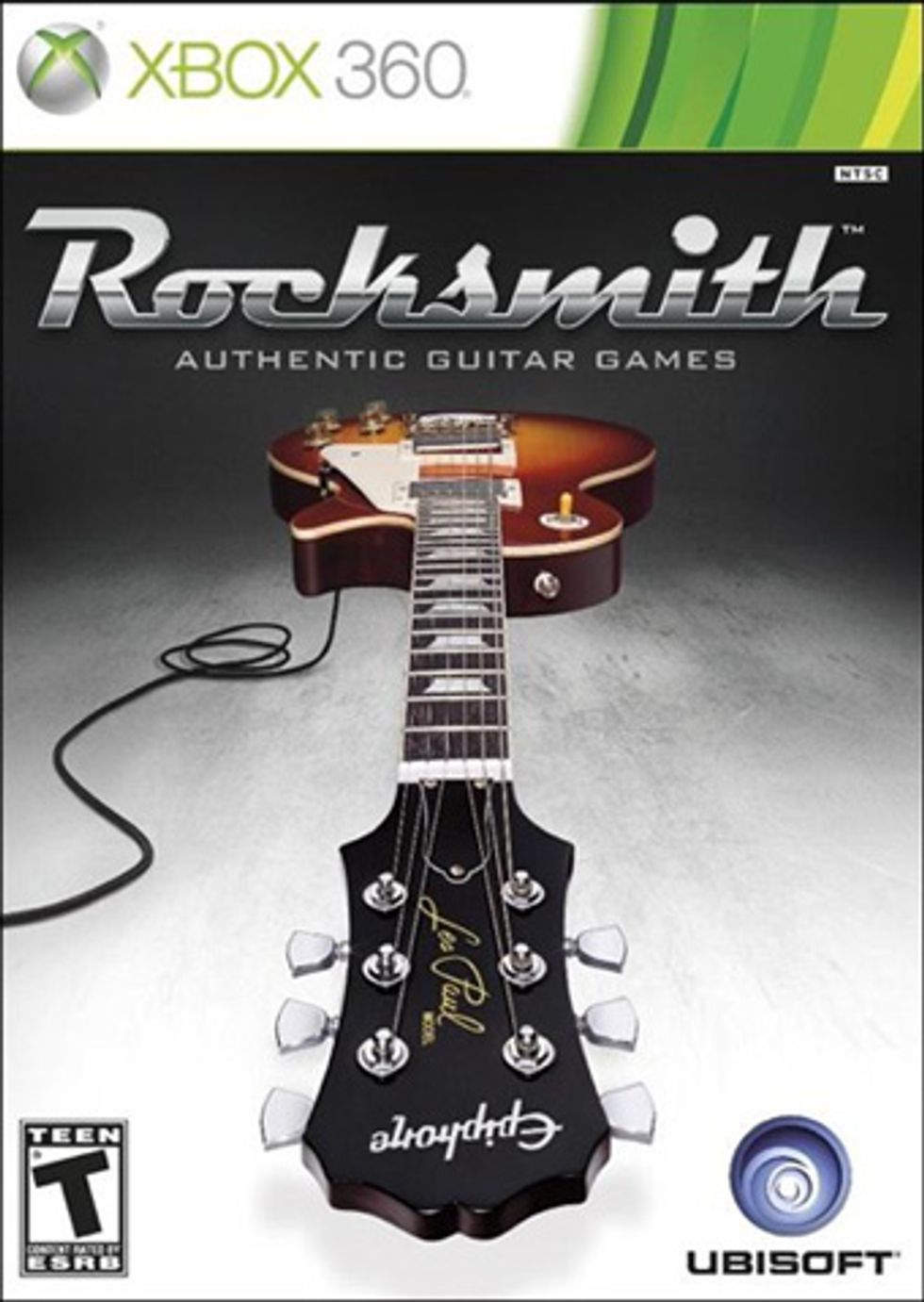

So, here is what is unusual about Rocksmith and sets it apart from Guitar Hero, et. al. While you are playing this game, you will also actually learn how to play an actual guitar (not the plastic versions) -- at your own pace.

If you've ever tried to learn guitar, and given up, you probably doubt that you could possibly learn by playing a game. But one of the reasons it's so hard to learn guitar, and other fretted string instruments, is that the traditional method for teaching people how to master them, in a word, sucks.

One reason is Tablature, which is a static form of musical notation that stresses where to place your fingers rather than musical pitch. It can seem counter-intuitive to students and therefore extremely difficult to grasp.

Compare that with how Rocksmith teaches you guitar, as demonstrated to me by the team's creative director, Paul Cross, and senior producer, Nao Higo, both of whom have backgrounds as successful game developers but neither of whom had ever before played the guitar.

Based on technology developed by GameTank, a local sound technology venture that was acquired several years back by Ubisoft, Rocksmith employs software that accurately recognizes the many tones of a guitar, and the first thing the game prompts you to do when you sign on is make sure your instrument is in tune.

Then, viewing as if through the back of the guitar, the program presents you with lanes representing the 22 frets, down which notes flow toward you, very slowly at first. If you miss a note, the game stops to let you catch up.

As you start hitting the notes properly, the game speeds up, expands the range of frets you have access to, and helps you build the necessary muscle memory to relatively quickly learn to play that song by heart. Cross told me that it takes an average beginner maybe an hour and a half to learn, say, 70 percent of a song.

Using the game, Cross and Higo both demonstrated that they can now indeed play some of the 50 pre-loaded songs on guitar with Rocksmith, and they say that every person who has tested the product so far, including many others with no previous musical experience, have learned how to play the guitar in this way as well.

"This is like the opposite of practicing," says Cross. "Practicing isn't fun. Rocksmith is." It's easy to see from his wide smile as he rocks out that here is a game developer who is most definitely enjoying his job.

Which brings me back to why I consider this game potentially revolutionary in its impact. As the parent of a number of teenagers who have tried to learn to play guitar in the past, without notable success, I sense that Rocksmith may represent a breakthrough in how people can learn all sorts of new skills through gaming technology.

Plus, IMHO, the world can always use a few more rock stars.

As I was watching the demo in Rocksmith's studio space behind the main company offices at 625 Third Street, I couldn't help but think how appropriate it was that this new tool for helping people discover what Laurent Detoc calls their "inner rock star" was emerging from the very same building where my colleagues and I published Rolling Stone, the bible of rock, back the 70s.

In honor of that history, at Ubisoft, there's a meeting room named after Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, right on the spot where Gonzo Journalism first met Rock 'n' Roll.