Rich Collins’ future was told to him as a dish of braised endive cooked on the stove: “This is what you ought to grow! I pay four bucks a pound for it.” The year was 1978, and that sage was chef Dick Vickers, boss of a then-dishwasher who dreamed of becoming a farmer.

Today, Collins, 53, is the largest endive grower in the country. At 5 million pounds a year, his California Endive Farms in Rio Vista—two hours northeast of San Francisco—produces 99.9 percent of the state’s endive for customers that include Alice Waters, Thomas Keller, and Whole Foods. “Early on, we had epic failures: our entire stock rotted,” he recalls. Though he spent nearly a year apprenticing with farmers in Belgium, Holland, and France, Collins endured three discouraging years of losses before turning a meager $7,879 profit in 1986. He admits it took ten years on his own before he finally nailed it. “In farming, you have to wait a year to adopt the lessons you learned the previous year. Like everything, the devil is in the details,” he says.

The key was learning how to grow and store a strong chicory root. In the growing process, which begins in the open field and ends in a pitch-black room where the roots are forced to grow sans photosynthesis, Collins can attest that there are “at least thirty steps where you can screw it all up.” But after years of practice, the tables have turned: European endive growers are visiting Collins’ farm. And they are impressed by, even jealous of, the quality of his crops.

This Thanksgiving, Collins celebrates 30 years since his first harvest. You can count on there being endive on the dinner table, cooked in butter and braised with chicken stock, finished with a whisper of nutmeg in a nod to chef Vickers—a tasty tribute to the man and dish that inspired it all.

Rich Collins has cornered the endive market this side of the Mississippi through his dogged insistence on making a living selling a vegetable that is one of the world’s most challenging crops to grow.

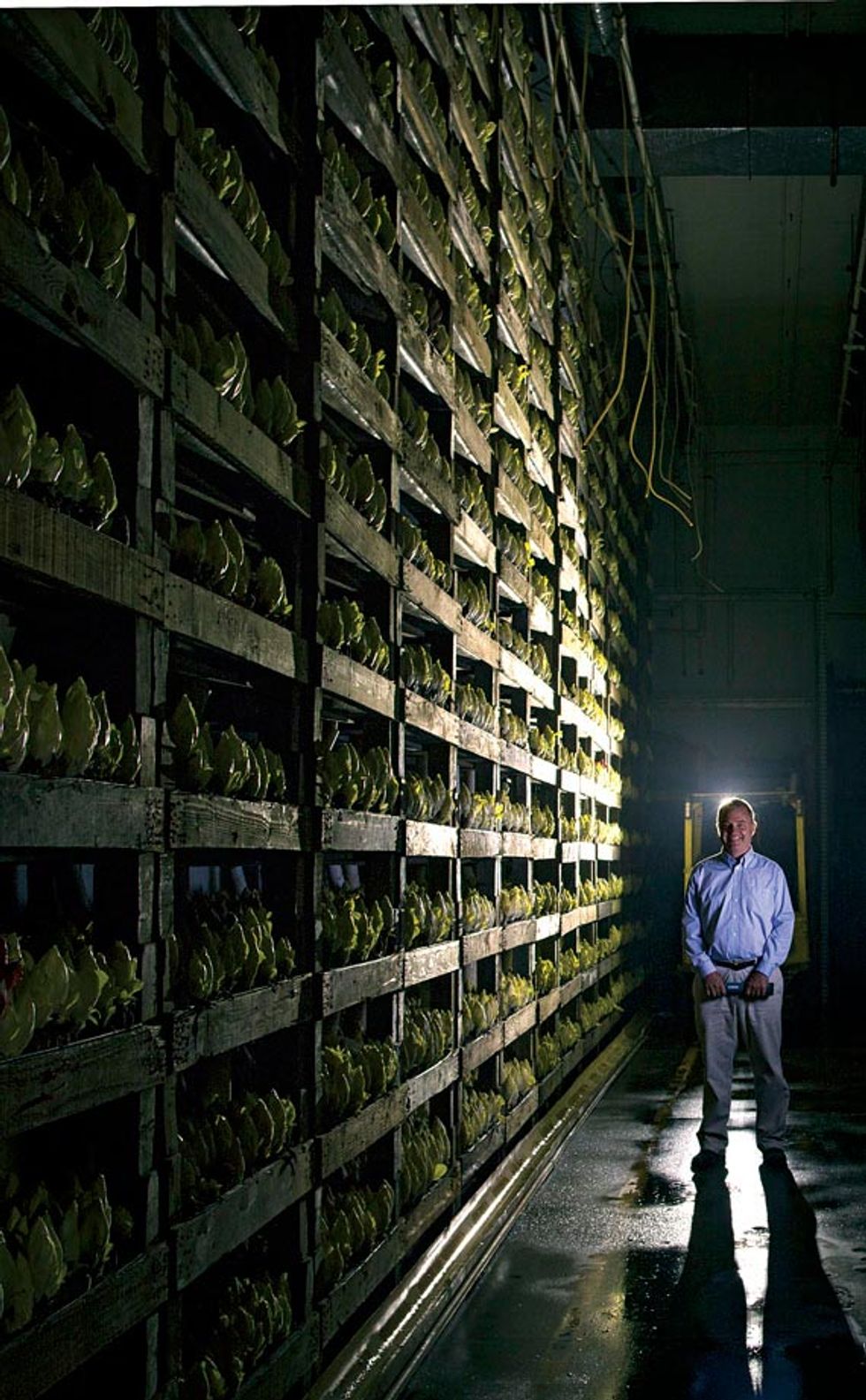

California Endive Farms plants 250 acres of red and white chicory seeds. For the next 150 days, the seeds grow a lush canopy of bitter leaves and a thick taproot, which resembles a parsnip. At harvest, the farmer first mows the foliage, leaving the bud and one inch of leaves on top of the roots, before digging the chicory up like potatoes. The endive will eventually grow from the bud of this chicory root. Collins stores the roots in his massive, 20,000-square-foot refrigerated warehouse to mimic winter conditions and preserve the roots for as long as a year.

Every day, 100,000 chicory roots are taken from the cold room, arranged in trays, and moved to a pitch dark “forcing room” kept at 59 degrees. Collins bears the chilly temps. When all goes according to plan, the root sends up a single shoot of tightly wrapped leaves. After about 28 days, the endive is ready for harvest. The endive snaps off the chicory root easily, and loose leaves are trimmed from the endive head before it is packed and shipped.

Alice Waters uses Collins’ endive as an edible boat for halibut ceviche (click here for the recipe!).

This article was published in 7x7's November issue. Click here to subscribe.