It was 5am and the night sky had only just begun to brighten. The wind and the wild birds sang in the eucalyptus trees, and from the deck of my cottage, I could make out the little flecks of white far below where, here and there, the ocean licked at the base of a great grey rock a few hundred yards offshore.

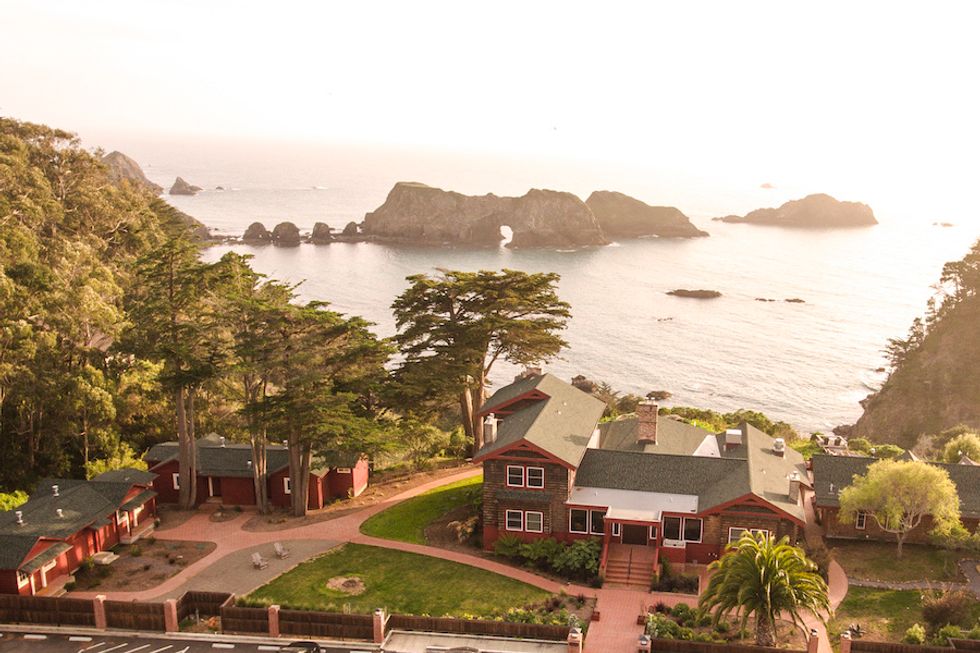

In the half a lifetime I'd lived in California, I'd been to the Mendocino coast more times than I could count, but the fact that on this particular morning I felt more connected to the place than ever had less to do with the slow accretion of familiarity than it did with what I'd eaten the night before, and with Matthew Kammerer, the chef at The Harbor House Inn, a historic property which reopened this month in the town of Elk.

Kammerer begins his workday in his garden, although his garden is somewhat more expansive than most, encompassing a pristine cove where, at low tide, he can gather a menu's worth of seaweed in a matter of minutes; the nearby fields and forests that supply his kitchen with everything from fungi to wild greens; and the intensively cultivated grounds of the inn, where impressively vigorous vegetables of every hue and stripe beckon from a phalanx of handsome raised beds, and where, on closer inspection, even the prettiest stands of leaf and flower prove to be careful assemblages of aromatic herbs.

If it all seems rather Edenic, no one seems more appreciative than Kammerer, who discovered the area while working his way up from commis to executive sous chef at Saison in San Francisco. On his rare days off from the three-Michelin-star restaurant, he made a ritual of driving to Elk and walking out to a bluff where, with the sea on one side and the redwoods on the other, he felt wonderfully grounded. It was a place he could see himself living and working if the right opportunity ever arose, for just as he was intent on learning as much as possible at Saison, he had also been nursing the idea of running a restaurant at a remote country inn like The Royal Mail Hotel in Dunkeld, a small town in southeastern Australia, where he had worked some years earlier. Late last summer, Kammerer became aware of The Harbor House Inn, and sent his CV posthaste. His partner, Amanda Nemec, who had likewise fallen under the spell of the North Coast and had long toyed with the thought of running a small business, left a job in Silicon Valley to become the inn's general manager.

My dinner reservation was on the early side, timed to allow maximum enjoyment of the sunset. The waning sunlight, filtered through a dense fog, gently illuminated the airy, high-ceilinged dining room clad in rich, warm redwood, an eminently appropriate material as the inn had been built in 1916 by the Goodyear Redwood Company.

Things kicked off not with Champagne but with a cider called Sur la Mer, from the family-owned winery Drew, in Philo. Made from organically farmed Gravenstein, Philo Gold, and Rhode Island Green apples, it was hazy straw-yellow gold with a fine pine-citrus aroma and a pleasingly sharp and slightly vinegary flavor somewhat reminiscent of kombucha.

The zing of the cider harmonized nicely with the first dish: copper rockfish with horseradish and arugula. Bought live from local fishermen and dispatched in the kitchen with the Japanese ikejime technique, the fish was intensely fresh, meaty and fatty, and nestled in a jelly made from rice wine vinegar, white soy sauce, preserved grapefruit juice, lime peel and dried, fermented and smoked skipjack tuna. The aftertaste was a magical thing, a mingling of fat, salt, and the sea—a fish dreaming of bacon.

It's hard to convey my excitement at the second course—bread and butter—things you rarely see on tasting menus in a day and age when many chefs seem to be prioritizing proteins over starches. Kammerer agreed, attributing bread's disappearance to the perception that it isn't a "luxury food." But of all the gustatory experiences, what's more luxurious than biting through a brilliantly crisp, crunchy crust into a chewy-spongy sourdough slathered with ultra-creamy butter seasoned with the umami richness of grilled sea lettuce? This is a rhetorical question.

The next dish, introduced as "layers of Dungeness crab," was served in a small, ceramic cup. At the bottom of the cup was a thin layer of chawanmushi, a light egg custard with a very delicate crabby flavor derived from the crustacean's shell; in the middle, shredded meat lightly poached in a mix of seawater and kelp-infused water; and topping it off, the meat from the claw, likewise poached and then slowly finished over charcoal. Apart from its deliciousness, the dish was a compelling study in the purity of flavor, which is one of the unifying themes of Kammerer's cooking.

There was a clue, when the waiter balanced a pair of chopsticks on a crescent shaped sliver of abalone shell, that the next course was going to involve one of my favorite sea creatures. In a kind of marine analogy to rabbit with parsnips, Kammerer served abalone with its staple food: seaweed. Tenderized to perfection by a swift pounding, the abalone, garnished with wakame and rockweed, stewed invitingly in a kelp broth seasoned with fermented wild mustard leaves. Making my way through the dish, I found myself particularly captivated by the seaweeds, the rockweed with its nubbly texture and soft, satisfying crunch, and the slippery-savory ribbons of wakame, which could almost be mistaken for well-buttered tagliatelle. An excitingly young and briskly tannic Mendocino Ridge AVA pinot noir, also from Drew, cut neatly through the dish's oceanic richness.

The menu took a vegetarian turn, first with a simple-looking arrangement of asparagus, peas, and fava beans, the flavor of each perfectly distinct; and then with a dish introduced as "potatoes steamed in coastal pine"—three tiny tubers imbued with the aroma and essence of pine needles, garnished with tender miner's lettuce snipped from the woods that morning, and dressed in a light sauce made from grilled onions and shio koji (a seasoning made in this case from cultured rye berries).

If slightly more elaborate in its presentation, the last savory dish was as compelling as the rest: a juicy fillet of grilled black cod, graced with a similarly succulent cut of cardoon; beside it, in a little wooden box, crispy bits of the steamed, dried and fried skin of the same fish, seasoned with a tangy spice blend made from wild and cultivated plants; in three gilded bowls, some lightly fermented carrots, radishes, and cabbage; and in a small, wood-handled cast iron pan, lusciously nutty Mendocino-grown wild rice topped with a scatter of tender New Zealand spinach.

A little later on, savoring the final fleeting notes of a dollop of citrus marigold ice cream as the sky went from gray to black, I sensed a shift had taken place. For in spite of all the years and the countless times I'd been to Mendocino and marveled at the beauty of its forests and its meadows and the sea, it wasn't until that night, in a little inn high on a bluff, that I'd ever truly tasted it. // The Harbor House Inn, 5600 South Hwy 1 (Elk), theharborhouseinn.com