In her seminal text, "Scenes of Subjection," Saidiya Hartman describes how emancipation transformed enslaved Black people from chattel property to burdened and still unfree subjects with three simple words: "Emancipation instituted indebtedness."

The debt describes the evolution of bondage from the hold of the slave ship and confines of the plantation to the prison, which is described by prison studies scholar Dennis Childs as a "land-based slave ship." Living in slavery's afterlife, living in what Christina Sharpe describes the wake, means living in a state in which "we, Black people, become the carriers of terror, terror's embodiment, and not the primary objects of terror's multiple enactments." The prison, then, functions as a space into which terror — Black people understood only as threatening, laboring bodies (not people) — is confined.

While the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) remains closed during this COVID-19 pandemic time, it is presenting "Meet Us Quickly: Painting for Justice from Prison," a showing of the works of 12 artists presently or formerly incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison, as a digital exhibition. Replacing the institutional wall text describing each contribution is a biographical text written by the artist, allowing them to present their identities, ideas, and experiences, in their own words. This kind of autonomous self-presentation is an opportunity overwhelmingly refused to incarcerated people and communities affected by policing and other racist and classist carceral structures.

In Nicole Fleetwood's recently published book "Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration," she explores the creativity and artistic expression that nevertheless occur within structures of violence and captivity. The book seeks to make visible currently and formerly incarcerated artists that are made deliberately invisible by both the twinned social death of the prison and exclusionary gatekeeping of art institutions. Her book highlights how the work produced within the carceral space — prison art — is shaped in two key ways. Work is firstly influenced by penal time, the temporalities that completely transform how one relates to themselves and the people and spaces and things (or lack thereof, in the case of solitary confinement) surrounding them. The work is secondly informed by penal space, the physical structures and strictures of imprisonment navigated and inhabited by incarcerated peoples on a daily basis.

The show was curated by Rahsaan "New York" Thomas: a writer, the co-host of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated podcast Ear Hustle, and the co-founder of Prison Renaissance, an arts journal and social movement that seeks to center the leadership, political ideas, and art practices of incarcerated people in activism and cultural production related to criminal justice reform. In his essay "The Art of Proximity," his curatorial statement for the show, he narrates his motivation for the show — exclusion. He begins: "According to the laws of physics, everything that occupies space is matter, but when you're serving a life sentence, it feels like you defy physics — you occupy a cell but don't matter to society." Invoking both the ideas of penal time and space, the longevity of one's sentence diminishes their voice, the visibility, and the mattering — both physically and metaphysically — of individuals punished by the state. Art, an allegedly universal language of aesthetics and visuality, is one means by which he envisions people on the inside gaining proximity to us non-incarcerated people outside who have the social power to structure social movements and artistic spaces. It is a means of communicating the vulnerability and suffering of presently incarcerated people to COVID-19; it is an expression of the thoughts and memories and ideas and inspirations of people cordoned off from the world (and even from one another), some of them indefinitely.

The displaying of these stylistically varied works by largely self-taught artists in a traditional white cube museum institution is also a bridging of the completely fabricated boundary between the insider and outsider artist — between conventionally understood and appreciated artistic visions to those methodically withheld and erased from public view. Art, ideally, is a means of growing our conceptions of incarcerated people beyond political moralisms about criminality and punishment — that is the very essence and philosophy of Prison Renaissance. From more realistic portraiture, gritty graphic novels, and beautiful landscapes to neo-constructivist configurations, mural drawings, and representational homage, the twenty-one exhibited pieces of art communicate urgent interiorities and perspectives drowned out by an art world too fixated purely on aesthetics and perfectly scripted written accompaniment. It is, fundamentally, a show about human resilience, the enduring nature of creativity, and the potential for growth within our social justice movements.

Eclectic in influence, some works in this exhibition nod to pointillism and neo- constructivism and others honor the importance of the artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

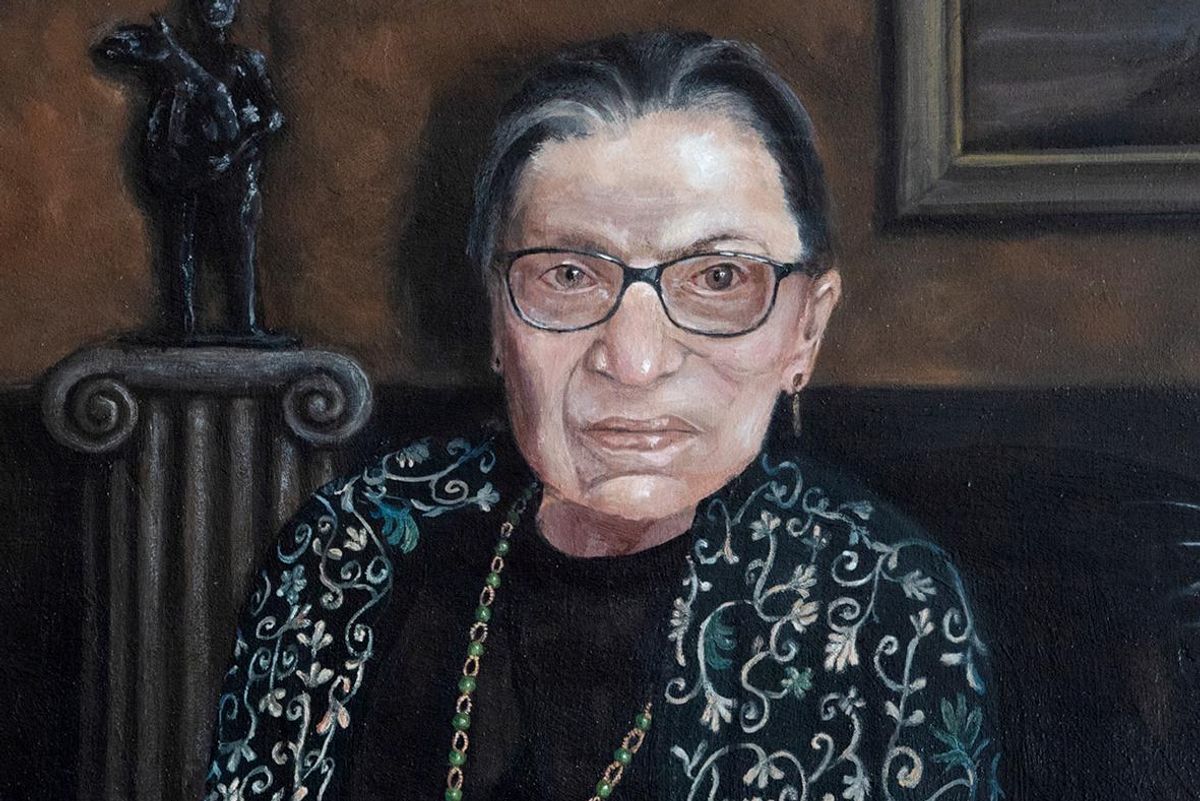

Gerald Morgan contributes "Pyramids," a painting that captures the vision of Aaron Douglas, a 20th century Black artist. Gary Harell, incarcerated for 42 years and counting, blends block printing with pointillism to create vivid portraits. Orlando Smith, a tattoo artist prior to being given eight life sentences under the Three Strikes Law, contributes a number of finely detailed graphic novel illustrations, powerfully depicting life behind bars. Tafka Clark Rockefeller paints oil and acrylics and believes that all art should deliberately and meaningfully break at least one rule. His style, which he calls Neo-Constructivism, is clearly on view in his painting "Make Skeletons Dance." Bruce Fowler's "Ruth" is a richly painted portrait of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Fowler writes, "My inspirations come from internal struggles that haunt me, places I dream of escaping to, and people I admire, which led me to paint Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She suffered terrible losses and conquered unimaginable odds to become the most powerful woman in America — a woman I have great respect for. I am honored to have the opportunity to paint her; this is coming from the most unlikely admirer."

"Meet Us Quickly: Painting for Justice from Prison" is presented in partnership with Flyaway Productions and Prison Renaissance; ongoing at The Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD), moadsf.org.

This article was written by Zoé Samudzi for SF/Arts Monthly.

More from SF/Arts Monthly: