With three films slated for this spring—True Story, I Am Michael, and Wim Wenders's Everything Will Be Fine—James Franco continues to be the busiest man in show business.

Actor, director, producer, writer, poet, professor, social media maven, and cultural provocateur, he also continues to challenge us by challenging himself about preconceived concepts of sexuality and how they fit contextually into his art. So it was no surprise when he accepted this challenge to sit down with himself to discuss his life together.

Straight James: Hey, bud, this is weird. You’re interviewing yourself.

Gay James: Yeah, I know. Who’s doing the interview, and who’s being interviewed?

SJ: Let’s just have a convo, and we’ll both try to get to the bottom of James.

GJ: Okay, deal. But my question is, who is the real James, and who is the mask?

SJ: I guess that’s what everyone wants to know, right?

GJ: I guess, but I also guess that even though I have this public persona that is all wacked out and hard to pin down, or annoying, or whatever, in some ways I’m still more real than if I were just hiding behind a façade or whatever.

SJ: Façade. Meaning, like, a movie-star façade?

GJ: Yeah, like I just hide behind my movies, and try to look cool, and don’t talk about anything of substance, and just give bland answers to everything like an athlete. “Yeah, we played with heart out there tonight. Really brought it.”

SJ: OK, so, good place to start. Let’s get substantial: are you fucking gay or what?

GJ: Well, I like to think that I’m gay in my art and straight in my life. Although, I’m also gay in my life up to the point of intercourse, and then you could say I’m straight. So I guess it depends on how you define gay. If it means whom you have sex with, I guess I’m straight. In the twenties and thirties, they used to define homosexuality by how you acted and not by whom you slept with. Sailors would fuck guys all the time, but as long as they behaved in masculine ways, they weren’t considered gay. I wrote a little poem about it.

Gay New York

Gay New York

Is the name of a book

About Gays in New York.

From the nineteenth century on.

Back in the thirties

Before the Second World War,

“Gay” wasn’t even a word,

Unless you meant “happy.”

You were “queer”

If you acted queer.

But you could turn a sailor

And still be straight

As long as you didn’t speak

With a lisp or wear a dress.

Funny how a concept can change

A whole culture.

We have to worry

About who we have sex with.

Weird how one little blowjob

Will make you a fag nowadays.

SJ: Yeah, Hart Crane fucked a lot of those sailors.

GJ: OK, Hart Crane . . . so, when you played him in the film you directed, The Broken Tower, you fellate a dildo on-screen and then have simulated sex with Michael Shannon. What’s up with that?

SJ: What’s up with that? Well, I wanted those scenes to be explicit, for two reasons. One, I knew that Crane was a openly gay man in a time when that was rare, and he was so up front about it he scared his more conservative poetry friends, so those scenes were a way to parallel the in-your-face nature of Crane’s own sexuality. I also knew that the movie was going to be full of dense poetry, so I wanted to break it up a bit with some hot sex.

GJ: Okay, but didn’t you know that that would be the only thing the reviewers would talk about?

SJ: Of course, but that’s their shortsightedness. And once I went to film school and started directing my own movies, I realized that I was going to direct only movies that I really cared about in ways that I wanted, regardless of critique. As an actor I have been in huge blockbusters like Spider-Man and Planet of the Apes, and in critical hits like Milk and 127 Hours, as well as in successful comedies likePineapple Express and This Is the End, so I know all sides of success. But when directing my own projects, the primary focus is the art. Yes, I want people to see them, and, sure, I’d like people to like them, but my primary allegiance is to the work itself.

GJ: Okay, whatever you say. But you’re also a goofball, especially on your Instagram account. Do you want people to think you’re gay? Wouldn’t it be a good thing if you were just a straight dude, like Ryan Gosling, just straight and cool?

SJ: Why would you say that it was a good thing that people would consider me straight? I actually like it when people think I’m gay; it’s a great shield. Like the guy in Shampoo or the play thatShampoo is based on, The Country Wife by Wycherley.

GJ: What do you mean? You want to be able to go around screwing other people’s wives by pretending to be gay?

SJ: No. I guess I mean that I like my queer public persona. I like that it’s so hard to define me and that people always have to guess about me. They don’t know what the hell is up with me, and that’s great. Not that I do what I do to confuse people, but as long as theyare confused, I get time to play.

GJ: Some people think it’s annoying.

SJ: If I’m so annoying, why do they write about me? If they were truly sick of my shit, they would just ignore me, but they don’t. I don’t do what I do for attention; I do it because I believe in what I do. Of course, some of it is tongue-in-cheek, but that’s just a tonal thing. It’s not like I call the paparazzi on myself or anything like that; I’m just having a conversation with the public. If you don’t want to be part of the convo, check out. If you do, cool.

GJ: Okay, but some people tell you to just screw a guy, and then you’d get over all this gay art stuff, like playing the gay poet Hart Crane or another gay poet, Allen Ginsberg, or directing the movieInterior. Leather Bar, which has actual gay sex in it, or painting paintings of Seth Rogen naked. Maybe if you just fucked a guy, you’d get over all this exoticizing of gay lifestyles?

SJ: Maybe sex with a guy would change things, but I doubt it. Like I said, I’m gay in my art. Or, I should say, queer in my art. And I’m not this way for political reasons, although sometimes it becomes political, like when I voted for same-sex marriage, etc. But what it’s really about is making queer art that destabilizes engrained ways of being, art that challenges hegemonic thinking.

GJ: But inevitably people will think that you’re gay; they will think that you’re in Milk, and Howl, and The Broken Tower, and Interior. Leather Bar because you are actually gay. That all these projects are ways of playing gay hide-and-seek.

SJ: These are all works of art, and art is free; art is its own realm. Of course, they can be read through a biographical lens and, of course, through something like Interior. Leather Bar uses my persona to talk about some of these very issues, but they are still works of art and not exactly nonfictional statements about who I am.

GJ: Is this interview a nonfictional statement about who you are?

SJ: Yes and no. Yes, in the sense that I am answering as James Franco, but no in the sense that it is a public statement in an entertainment magazine, which means that it is part of my public persona and not my private veridical self—and even if it were in theNew York Times, it would be the same; it would be an expression of my public self.

GJ: Well, why don’t you stop playing games and give us a little of your private self?

SJ: Kind of impossible, don’t you think? As soon as I share it, it becomes public. Here’s a little poem back at ya.

Fake

There is a fake version of me,

And he’s the one that writes

These poems.

He has an attitude and swagger

That I don’t have.

But on the page, this fake me

Is the me that speaks.

And this fake me is louder

Than the real me, and he

Is the one that everyone knows.

He’s become the real me

Because everyone treats me

Like I’m the fake me.

GJ: And why is the public self any less sincere than the private self?

SJ: That’s a good question. I guess, for me, I’ve disowned it a little bit. When I was young, I tried so hard to control the public’s perception of me, but I found that to be a waste of energy, partly because I couldn’t control how people saw me and partly because I stopped caring.

GJ: You don’t care if people don’t like you?

SJ: Sure, I care, but I don’t let that stop me from doing something I believe in. And let’s say all my fans suddenly turned against me overnight. If I were to be honest, I couldn’t complain, because I have had an awesome life so far. I’ve had a life many people dream about, and if it went away tomorrow, I could still say I had my share of the good stuff.

GJ: Is that why you teach? To give back some of the good stuff to others?

SJ: Duh.

GJ: Want to elaborate on that?

SJ: Sure. I teach to stop thinking about myself for a bit. But also because I find the classroom to be a very pure place, largely unaffected by the business world. I like people who still dream big, who are consumed by their work. And that’s how most students in MFA programs are.

GJ: Okay, last question. What do you say to people who criticize you for appropriating gay culture for your work?

SJ: I say fuck off, but I say it gently. This is such a fraught issue, and I am sensitive to all its aspects. But first of all, I was not the one who pulled my public persona into the gay world; that was the straight gossip press and the gay press speculating about me. I really don’t care what people think about my sexuality, and it’s also none of their business. So I really don’t choose to identify with my public persona. I am not interested in most straight male-bonding rituals, but I am also kept from being fully embraced by the gay community because I don’t think anyone truly believes I have gay sex.

GJ: Oh, some do, believe me.

SJ: Well, good, I like that.

GJ: Why?

SJ: Because it means that I can be a figure for change. I am a figure who can show the straight community that many of their definitions are outdated and boring. And I can also show the gay community that many of the things about themselves that they are giving up to join the straight community are actually valuable and beautiful.

GJ: Okay, can we talk about Child of God for a minute? You adapted the Cormac McCarthy novel, and your buddy Scott Haze gives an amazing performance that’s already been singled out by the New York Times. It’s now on Netflix.

SJ: Yup.

GJ: So, what the hell, James? Necrophilia? This dude is out in the woods having relationships with dead people! Everyone is going to think you’re more crazy than they already do.

SJ: Well, let’s remember that it’s a faithful adaptation of a book by Cormac McCarthy, who won the Pulitzer and was in Oprah’s Book Club. But you’re right; it’s grizzly material. But I didn’t make the film because I was interested in sex with dead bodies; I did it because I was interested in who we are when we are alone and who we are when we’re intimate with another person. Lester Ballard is a character who has full relationships with his corpses— meaning he fills in both sides of the mental relationship, but he gets a body to interact with.

GJ: Sort of like this conversation with yourself, except there is onlyone body.

SJ: Shit, I’d love to fuck you. Would that make me gay?

GJ: You jerk me off all the time.

SJ: Yeah, but I’m thinking about women when I do it or watching straight porn.

GJ: So, I know tons of gay guys who watch straight porn.

SJ: Anyway, this interview is going a little south, and I don’t think my publicist will appreciate us talking about porn.

GJ: FINE, whatever, one more question.

SJ: You said the other question was the last.

GJ: Well, you have a lot of fucking projects to promote, and your publicist wants you to talk about all of them.

SJ: Don’t tell me what my publicist wants.

GJ: Why not? She’s my publicist too.

SJ: Yeah, but she wants you to stay out of the public eye because you’re gay.

GJ: That’s bullshit. Robin Baum doesn’t give a shit what I do.

SJ: I don’t know about that, but anyway, what’s your question?

GJ: Tell me about this new film directed by Justin Kelly, one of the editors from Milk.

SJ: Basically, it’s about this guy, Michael Glatze, who was this huge gay activist in San Francisco in the early 2000s who worked for XYmagazine and would go around to high schools telling kids it was okay to be gay. And then he had this huge turnaround, and found God, and then became Christian, and then was ordained as a Christian minister, and now he’s married to a woman. At first he turned on his ex-boyfriend and all his friends and said that if you’re gay, you’re going to hell. But I think he’s since pulled back a little.

GJ: Well, that’s nice of him.

SJ: Ha, yeah, he went a little extreme for a minute.

GJ: Hmmm, and why did he go straight?

SJ: He thought he was going to die.

GJ: And why are you gay?

SJ: Because it’s more fun.

GJ: And why would you make that movie? I mean, what’s the point?

SJ: Well, it’s not as if it’s a movie that is itself anti-gay. It’s just a very interesting and unique way to examine the way that straight and gay is defined, by others and how we define ourselves.

GJ: (thinks for a minute) You know, you’re pretty arrogant.

SJ: Why do you say that?

GJ: I don’t know, this whole interview. Like, how dare you interview yourself? And it’s just so annoying because you’re always trying to be so meta, like in This Is the End.

SJ: Dude, this interview wasn’t my idea. I was asked by this magazine to interview myself. And I didn’t write This Is the End, but I’m glad I was in it. It was a way to talk about a lot of stuff without being threatening because it was comedic.

GJ: Okay, let’s kiss in the mirror again.

SJ: You got it, baby.

(They kiss.)

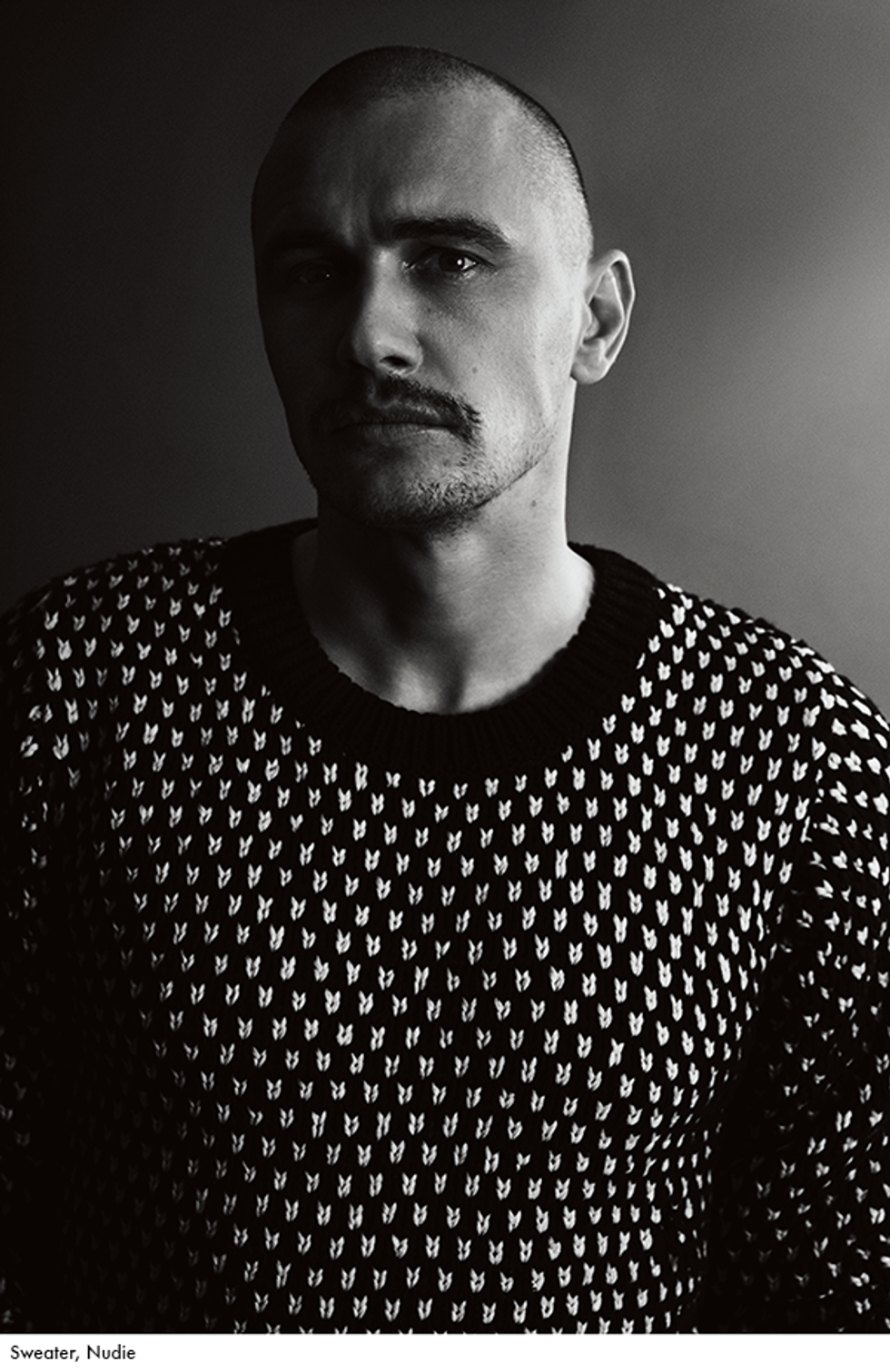

-Originally published in 429 Magazine. Photographed exclusively for FourTwoNine by Damon Baker

DigitalTech: Jeff Vogeding

DigitalTech Assistant:ThangTruong

Videographer: Gina Leonard

Photographer: Meeno

Stylist: Evet Sanchez

Stylist Assistant: Eric Soto

Groomer: Jamal Hammadi

To see more photos of James Franco in FourTwoNine, you can subscribe here or purchase the issue on newstands or at any Barnes & Noble.